Researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have identified a tenacious subset of immune macrophages that thwart treatment of glioblastoma with anti-PD-1 checkpoint blockade, elevating a new potential target for treating the almost uniformly lethal brain tumor.

Their findings, reported in Nature Medicine, identify macrophages that express high levels of CD73, a surface enzyme that’s a vital piece of an immunosuppressive molecular pathway. The strong presence of the CD73 macrophages was unique to glioblastoma among five tumor types analyzed by the researchers.

“By studying the immune microenvironments across tumor types, we’ve identified a rational combination therapy for glioblastoma,” says first author Sangeeta Goswami, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of Genitourinary Medical Oncology.

Glioblastoma immunotherapy clinical trial planned

After establishing the cells’ presence in human tumors and correlating them with decreased survival, the researchers took their hypothesis to a mouse model of glioblastoma. They found combining anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 immunotherapies in CD73 knockout mice stifled tumor growth and increased survival.

“We’re working with pharmaceutical companies that are developing agents to target CD73 to move forward with a glioblastoma clinical trial in combination with anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 checkpoint inhibitors,” says Padmanee Sharma, M.D., Ph.D., professor of Genitourinary Medical Oncology and Immunology.

Sharma and colleagues take an approach they call reverse translation. Instead of developing hypotheses through cell line and animal model experiments that are then translated to human clinical trials, the team starts by analyzing human tumors to generate hypotheses for testing in the lab in hopes of then taking findings to human clinical trials.

To more effectively extend immunotherapy to more cancers, Sharma says, researchers need to realize immune microenvironments differ from cancer to cancer. “Understanding what’s different in immune niches across cancers provides clues and targets for treating tumors,” Sharma says. “That’s why we did this study.”

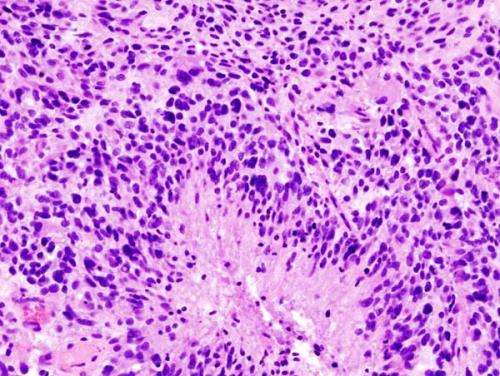

The team tracked down the population of CD73-positive macrophages through a project to characterize immune cells found in five tumor types using CyTOF mass cytometry and single-cell RNA sequencing. They analyzed 94 human tumors across glioblastoma, non-small cell lung cancer and kidney, prostate and colorectal cancers to characterize clusters of immune cells.

CD73 cells associated with shorter survival

The most surprising finding was a metacluster of immune cells found predominantly among the 13 glioblastoma tumors. Cells in the cluster expressed CD68, a marker for macrophages, immune system cells that either aid or suppress immune response. The CD68 metacluster also expressed high levels of CD73 as well as other immune-inhibiting molecules. The team confirmed these findings in nine additional glioblastomas.

Single-cell RNA sequencing identified an immunosuppressive gene expression signature associated with the high-CD73-expressing macrophages. A refined gene signature for the cells was evaluated against 525 glioblastoma samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas and was correlated with decreased survival.

The team conducted CyTOF mass cytometry cluster analysis on five glioblastoma tumors treated with the PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab and seven untreated tumors. They identified three CD73-expressing macrophage clusters that persisted despite pembrolizumab treatment.

Sharma and colleagues note the prevalence of CD73-expressing macrophages likely contributed to lack of tumor-killing T cell responses and poor clinical outcome.

Combination extends survival in mice

A mouse model of glioblastoma showed that knocking out CD73 alone slowed tumor growth and increased survival.

The team treated mice with either PD-1 inhibitors or a combination of PD-1 and CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Mice with intact CD73 treated with the combination had increased survival over untreated mice, while mice with CD73 knocked out lived even longer after combination therapy. There was no survival benefit from anti-PD-1 alone.

Source: Read Full Article