We all learned in school that the beams from X-ray machines pass right through soft tissues like skin and internal organs, but not dense materials like bones, right? Not so fast.

Researchers in Japan have figured out a way to use X-rays to tell doctors about those squishy parts as well, not just bones, in a similar way to how ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) work—but with much greater resolution.

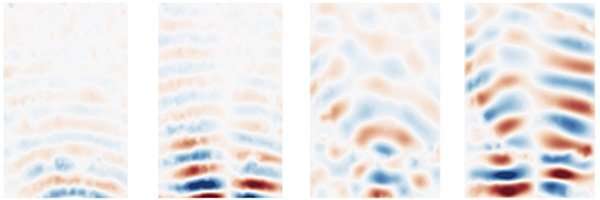

This greater resolution for the field of elastography—a non-invasive method of medical imaging that investigates the stiffness and elasticity of soft tissue—should allow healthcare professionals to identify much smaller and deeper tissue problems, such as lesions, than they can with ultrasound or MRI, the two main types of elastography used currently. The scientists published their results in March in the journal Applied Physics Express.

Although previous studies have suggested such X-ray elastography is possible in principle, this is the first time that any real-world visualization of stiffness using the concept has been demonstrated.

Ultrasound uses sound waves with frequencies higher than what humans can hear, and works by sending “shear waves” through us—the sort of waves that occur when you whip a rope up and down quickly. Shear waves travel faster through stiffer tissue than through softer tissue. Since cancerous tumors, lesions from cirrhosis of the liver and hardened arteries are stiffer than the surrounding healthy tissue, identifying where the waves pass through tissue more slowly, clinicians are able to spot these stiffer tissues.

MRI works in a related fashion, but via the use of very strong magnets to force protons in the body to align with a magnetic field. How long it takes those protons to make this move tells us a similar story about stiff or hard tissues.

Now, researchers have developed a technique to do much the same with X-rays instead. The advantage? X-rays can provide much greater resolution than ultrasound—on the order of tens of micrometers (millionths of a meter) instead of millimeters (mere thousandths of a meter).

“This greater precision doesn’t just mean identification of much smaller or deeper lesions,” said lead researcher Wataru Yashiro, an associate professor from the Institute of Multidisciplinary Research for Advanced Materials (IMRAM) of Tohoku University, “but, importantly for patients, because smaller lesions can be newer ones, potentially also much earlier on in a disease or condition.”

Source: Read Full Article