A wholistic tumour sampling method that more accurately detects genetic alterations in tumours, which are critical in allowing treatment to be personalised to each and every patient, has been developed by researchers from the Crick, Roche and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and published in Cell Reports.

Today, to help doctors select treatment options for cancer patients, a sample from their tumour can be DNA sequenced. This aims to find mutations in the DNA which mean the tumour is either susceptible or resistant to a specific treatment. The results of this test therefore have a significant impact on treatment choices and the patient’s prognosis.

However, the genetics of tumours are complex because they are often made up of different groups of cells which vary genetically and sit in different parts of the tumour.

Current sampling methods can miss this genetic diversity because they use tissue taken from just one small location in the tumour. In routine practice, on average, only five in a million cells from the tumour (0.0005%) are tested. This means that clinicians are making treatment decisions based on potentially incomplete information, which can lead to patients potentially missing out on the therapies that would give them the highest chances of survival.

Initially, the concept of improved sampling was tested in lung and bladder cancers, where a simulation of improved sampling reduced misclassification rates in deciding whether a patient was suitable for immunotherapy from 20% to 2% and from 52% to 4% respectively, when compared to current methods.

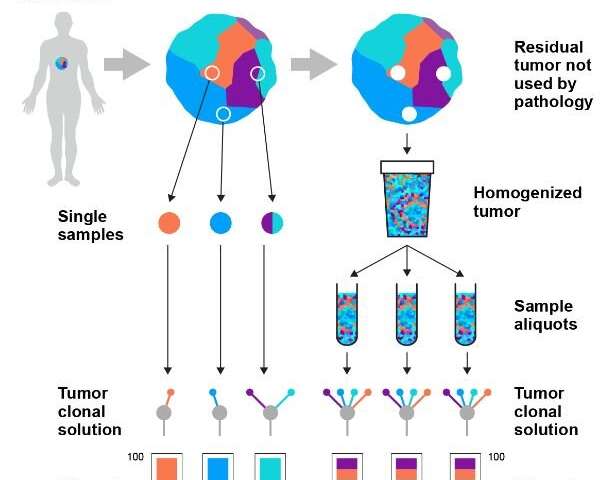

Based on this finding, they developed a technique called representative sequencing, which builds a more accurate picture of a tumour’s DNA. This works by taking the majority of the tumour removed at surgery—tissue that is not currently sampled and is routinely discarded—and mixing it so that cells from different areas of the tumour are more evenly distributed. A sample is then taken from this mixture to be DNA sequenced.

The researchers tested this new method in 12 patients with kidney, breast, colon, lung or skin cancer. Comparing the new and current methods, they found that representative sequencing gave far more consistent results, as it avoids the bias of looking at just one small part of the tumour tissue. Instead, the new method is able to capture information from a well-mixed representation of the whole tumour, meaning much more data is collected which is also of better quality. As an analogy, the new test takes a higher viewpoint and is more like a police search using a helicopter, rather than tracking a criminal just from one location on the ground.

The method, which was developed in partnership with researchers from the Crick, Roche Diagnostics and The Royal Marsden and published in Cell Reports is being further tested in 500 tumours at The Royal Marsden in London to further establish its feasibility and utility. The researchers hope that, following successful results, it will be rolled out further.

“By equipping clinicians with more accurate information about a tumour, we hope our method will lead to patients and treatments being significantly better matched. Additionally, there is an opportunity for critical biological insights to be made by increasing the search space within each tumour,” says Samra Turajlic, group leader at the Crick and Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden.

Through extensive testing on a case of kidney cancer, the representative sampling method gave identical genetic results 95% of the time, compared to only 77% consistency with the current methods. Similarly, in a case of skin cancer the new method correctly identified a highly complex and difficult to treat cancer from the outset, whereas the current method missed important genetic information.

“This method is more accurate, has more reproducible results and has the same sequencing cost as the current technique. In fact, by introducing an extra, simple purification step, it could become much cheaper than the existing process. It could be a gamechanger for tumour sampling in hospitals and in research,” says Kevin Litchfield, lead author and bioinformatician in the Translational Cancer Therapeutics Laboratory at the Crick.

“Through this work, we’ve addressed a major obstacle for solid tumor diagnostics using a straightforward method that can be implemented in the clinic,” says Nelson Alexander, the project’s principal investigator at Roche Molecular Solutions. “It’s a great demonstration of the impact that collaborations between public and private institutions can have on longstanding challenges in healthcare.”

Source: Read Full Article