Sporadic and epidemic acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis represents a common disease in developed and developing countries alike. This syndrome, conveniently named “winter vomiting disease” due to its distinct seasonality and frequent occurrence of vomiting, has been described as early as 1929. At the time this illness could not be attributed to any known bacterial or parasitic pathogen, and many years have passed since the etiological agent was identified.

Although the viral etiology was presumed early, the discovery was hampered due to the inability to recover and propagate the agent in vitro. A major breakthrough occurred in 1968, when viral particles were found in human-passaged fecal material derived from an outbreak of acute gastrointestinal illness at an elementary school in Norwalk, Ohio.

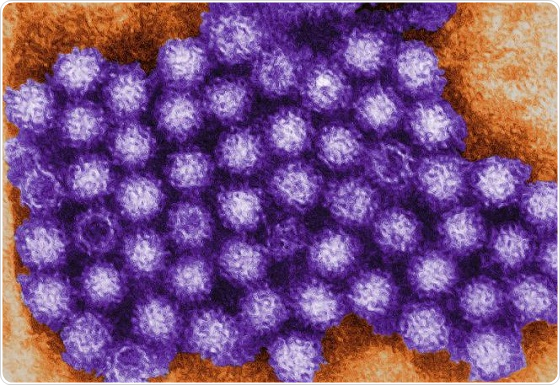

The aforementioned particles, described as 27 nm in their shortest diameter and 32 nm in their longest diameter, were the first viruses associated with gastroenteritis which were subsequently visualized and identified. They were initially named Norwalk virus, honoring the place of their discovery. Today these viruses are known as noroviruses, and they belong to the genus Norovirus, family Caliciviridae.

Structure of noroviruses

Noroviruses have a linear, 7.5kb, single-stranded RNA genome with a positive polarity which encodes three open reading frames (ORFs). The first and longest ORF encodes 194-kDa polyprotein cleaved by the virus protease 3C into six proteins, including RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. The second ORF encodes a viral capsid protein with a significant role in virus replication – VP1. The third ORF, considered the most variable region in the genome, codes for a small basic protein (VP2) interacting with the genome RNA when during virion formation.

The nucleocapsid is rounded and exhibits an icosahedral symmetry, and there is no envelope. Two major domains can be found in the capsid: the shell (S) and the protruding arms (P). The S domain represents the inner part of the capsid that surrounds the genome, while P domain forms the archlike capsomeres that are protruding from the virion.

The empty capsid is 38 nm in diameter and exhibits icosahedral symmetry with a triangulation number of three (the triangulation number is defined as the square of the distance between 2 adjacent 5-fold vertices). Capsid of the noroviruses is composed of 90 dimers of capsid protein, forming a shell from which 90 archlike dimers protrude.

Pathogenesis and clinical features

Infection with noroviruses generally manifests a mild and self-limiting illness. The onset of the disease can be either gradual or abrupt, usually within 12-48 hours after exposure. Vomiting is often the introductory symptom, which is swiftly followed by fever (in up to one half of all the cases), abdominal cramps, watery diarrhea, as well as the other constitutional symptoms such as headache, chills and myalgias.

Illness has a median duration of 24-48 hours with ranges up to 77 hours, but it can last longer in nosocomial outbreaks and among children younger than 11 years of age. The most common complication of the disease is dehydration, namely in young children and the older adults. Asymptomatic infections have been observed under experimental, as well as natural conditions.

The histopathological changes could be detected within 24 hours after virus challenge, with a pathognomonic sign of broadened and blunted villi in the small intestine. Furthermore, microvilli are shortened, and there is an infiltration of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells in the lamina propria. No histologic changes are observed in the gastric fundus, antrum or colonic mucosa.

Chronic diarrhea and shedding of the virus has been described in immunocompromised individuals. Recent research has suggested possible associations of norovirus infection with necrotizing enterocolitis in newborns, benign seizures in infants, and exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric patients. Finally, an increased mortality has been observed among the elderly in nursing home facilities.

Sources

- http://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/about/overview.html

- http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra0804575

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3150746/

- http://femsle.oxfordjournals.org/content/253/1/1.long

- www.scielo.br/scielo.php

Further Reading

- All Norovirus Content

- Norovirus Diagnosis

- Norovirus Classification

- Norovirus Transmission

Last Updated: Aug 23, 2018

Written by

Dr. Tomislav Meštrović

Dr. Tomislav Meštrović is a medical doctor (MD) with a Ph.D. in biomedical and health sciences, specialist in the field of clinical microbiology, and an Assistant Professor at Croatia's youngest university – University North. In addition to his interest in clinical, research and lecturing activities, his immense passion for medical writing and scientific communication goes back to his student days. He enjoys contributing back to the community. In his spare time, Tomislav is a movie buff and an avid traveler.

Source: Read Full Article