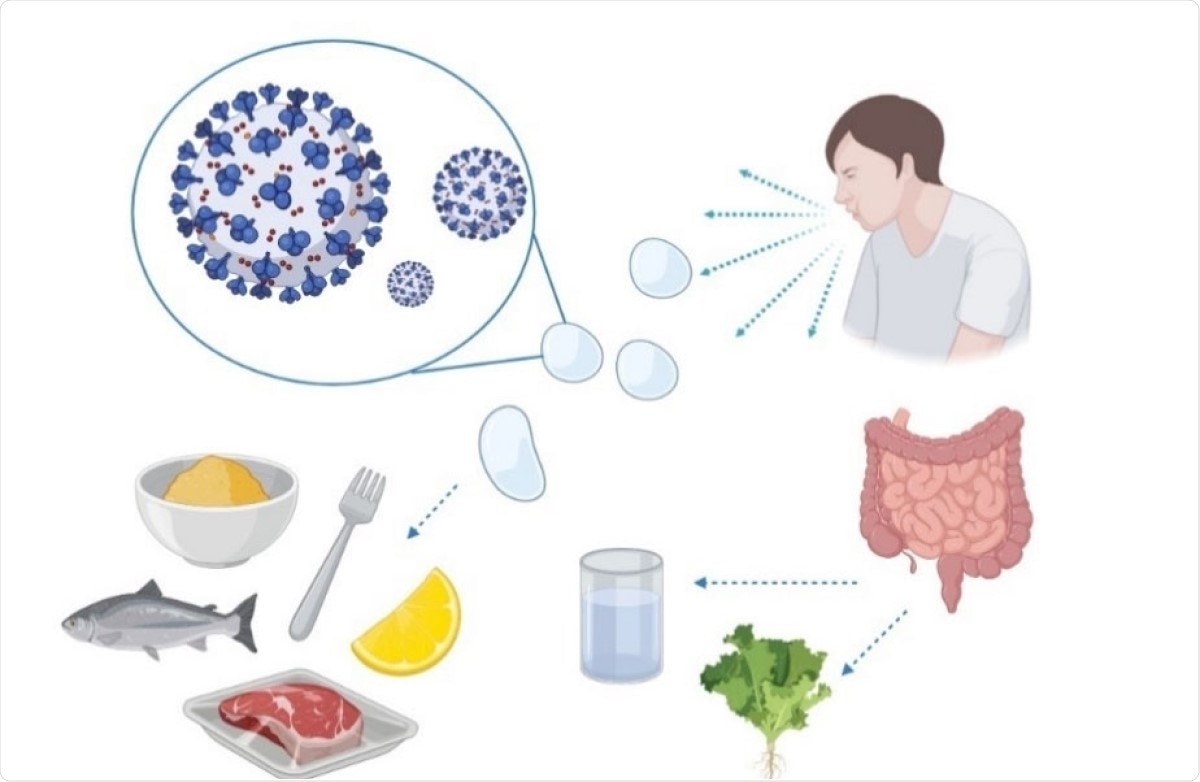

Caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the emergence of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China, was followed by a rapid and worldwide spread. This virus is unique in its long incubation period, allowing asymptomatic transmission for up to two weeks before the presence of the infection is recognized.

A new paper, in the journal Microbiology research, deals with the perceived and actual delivery of food items during this period. The frequent occurrence of diarrhea in children and adults infected by SARS-CoV-2, suggests it may signify the involvement of the gut in viral transmission.

Food packaging plants and COVID-19

Many human infections have been reported to have been associated with abattoirs and meatpacking plants in America and Europe, suggesting the role played by animal meat consumption in transmission. The presence of high aerosols and high-pressure water sprays help to carry the virus much farther than it would otherwise have gone.

Workers generate respiratory droplets at a much higher intensity due to their having to speak loudly in the noisy ambiance of the meat plant. Social distancing is at a minimum due to the nature of the work. Surface contamination by emitted virus particles is also a possibility.

SARS-CoV-2 survival for hours or days on surfaces at room temperature, as well as at low and freezing temperatures, has been established. This could lead to the spread of the virus by contamination of food and food packaging.

However, both the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) say they do not know of any case associated with foodborne transmission, unlike earlier outbreaks such as the SARS and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).

The current paper explores the zoonotic nature of the current pandemic, as well as its possible spread through the food supply chain. The researchers also examined the management of foodborne COVID-19, and possible ways to minimize contamination.

Zoonotic disease

The virus is known to originate in animals, but the exact nature of its leap across species barriers is unclear. Both earlier pathogenic coronavirus outbreaks originated in wet markets selling wild exotic animals. The current pandemic also is thought to have begun in a wildlife and seafood market in Wuhan, China.

The researchers found the possibility of useful, though partial, cross-reactive immunity due to stimulation of immune responses by several viral protein sequences and epitopes found in earlier animal coronaviruses.

This not only explains the spectrum of clinical disease in COVID-19, but could be used to develop diagnostic kits to distinguish COVID-19 from other respiratory infections. It could also help with vaccine development.

Viable in the cold chain

China prohibited the import of many frozen seafood and chicken-based foods, suspecting that new cases were being imported from the food packaging and processing plants, where outbreaks were being reported.

The viability of the virus in freezing conditions for over three weeks is established. An earlier study shows multiple episodes of food contamination through the cold chain of frozen food and storage plants. The researchers successfully contaminated various meats at three temperatures: 4, −20, and −80 °C.

Similar studies on pig skin and meat showed that the stable presence of the virus for 14 days at 4 °C carries a high potential for meat-transmitted infection and virus shedding. Fresh vegetables and fruit are also shown to carry the virus for up to 24 hours. After this point, infectious virus was not found, except on cucumbers, at any time within 72 hours.

Foodborne transmission remains hypothetical

Feco-oral transmission of the virus is possible, however, since the virus tends to persist in stool samples even after respiratory samples become negative. It has been found even in patients without overt symptoms of gut infection like diarrhea. However, the absence of consistent association between the consumption of contaminated food and COVID-19 prevents the classification of this as a foodborne virus. Neither has the virus been proved to cause a primary gut infection.

On the other hand, the regular epidemiological investigations used to track outbreaks of foodborne infection have not been applied to this virus so far.

Different surfaces

The virus has been found to persist on a variety of surfaces. It remains infectious in aerosols for up to 16 hours. It can survive at room temperature and with a relative humidity of 65% for days. On plastic surfaces, it remains detectable for seven days, but is markedly reduced in titer after 8 hours on copper surfaces.

It has been detected at 1% of the original dose on the outer surface of a surgical mask on day 7. Printing paper and tissue paper failed to show the presence of infectious virus after three hours, and after two days with treated wood or cloth.

For glass and banknotes, the virus reached undetectable levels on day four. The prolonged persistence on plastic, of which much food packaging is made, raises the issue of potential food contamination, spreading to the surfaces that come in contact with such packaging.

The infectious nature of the virus falls by less than one log on plastic surfaces, by 3.5log on glass, and by 6 logs on aluminum.

Temperature stability

The virus is stable in titer for eight hours at 4 °C, with a small drop at 30 °C. It declines within nine days at all temperatures and even remains infectious in the dried state for several days, even with changes in the ambient temperature. It is highly stable in cold conditions, especially in mucus and sputum on polypropylene surfaces, at 4 °C with a relative humidity of 40%, compared to temperatures in the twenties. At ‐20 °C, coronaviruses can survive for up to two years.

Thus, the cold food chain may be an ideal vehicle for the virus, transferring it from place to place.

Preventing foodborne transmission

Reinforcing hygiene measures and providing refresher training on food hygiene principles is necessary to eliminate or reduce the risk of food becoming contaminated by the virus from food workers.”

The FDA recommends four principles: clean, separate, cook, and chill food. Social distancing is also important, among these measures aimed at preventing infection of food industry workers and customers, and maintaining robust cleanliness and sanitation in the surroundings of this industry.

Viral inactivation

Several methods may be used to inactivate SARS-CoV-2. This includes gamma rays and ultraviolet radiation, either alone or along with riboflavin, and using UVC rather than UVA. Sunlight can produce rapid inactivation, with 90% inactivation in saliva suspensions, or in culture, within seven and 14 minutes, respectively. Inactivation occurred much faster with UVB compared to darkness.

Thus, exposure rates may be quite different depending on the setting, whether outdoor or indoors.

Ozone can also be useful, reducing viral titers by more than 90% on multiple surfaces, when used at a concentration above toxic levels. Heating also denatures proteins, achieving complete inactivation with 5 minutes at 70 °C.

Safe packaging can also be accomplished using nanomaterials to create biopolymers containing virucidal compounds, chemical release nanopackaging, and packaging with nanomaterials containing viral disinfectants that generate ions toxic to the virus. Such packaging could release copper, and thus produce permanent damage to the viral spikes and envelope, among other changes.

Similar nanoparticles could be used to make personal protective equipment (PPE) more resistant to the virus, such as silver nanoclusters. The application of this antimicrobial and antiviral compound exhibited virucidal effects.

Conclusion

Despite the low possibility of foodborne transmission of COVID-19, the review shows that the cold chain used in food processing and transport can encourage viral viability for years. Novel technologies can and should be applied to protect workers and prevent food contamination. Hygiene, and the use of PPE, could be early steps in keeping food safe.

- Ceniti, C. et al. (2021). Food Safety Concerns in “COVID‐19 Era”. Microbiology research. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres12010006, https://www.mdpi.com/2036-7481/12/1/6

Posted in: Medical Science News | Medical Research News | Miscellaneous News | Disease/Infection News | Healthcare News

Tags: Children, Cold, Cold chain, Compound, Contamination, Copper, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, Diagnostic, Diarrhea, Food Safety, Fruit, Hygiene, Meat, Microbiology, Nanoparticles, Ozone, Pandemic, Personal Protective Equipment, PPE, Protein, Research, Respiratory, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Skin, Syndrome, Vaccine, Vegetables, Virus

Written by

Dr. Liji Thomas

Dr. Liji Thomas is an OB-GYN, who graduated from the Government Medical College, University of Calicut, Kerala, in 2001. Liji practiced as a full-time consultant in obstetrics/gynecology in a private hospital for a few years following her graduation. She has counseled hundreds of patients facing issues from pregnancy-related problems and infertility, and has been in charge of over 2,000 deliveries, striving always to achieve a normal delivery rather than operative.

Source: Read Full Article