Kevin Wake has suffered three strokes. He is only 54. The first one taught him how humiliating an emergency room visit can be for Black people living with the blood disorder sickle cell disease.

It happened in Chicago, where the Kansas native was living in 1999. By the time he arrived by ambulance at the hospital he was immobile, unable to stand or speak.

“They started triaging me as Black male in his 30s who is either intoxicated or high on drugs,” Wake recalled recently.

All he could do was shake his head desperately. He finally caught the attention of a nurse and motioned he wanted to write something. “I scribbled three words, sickle cell stroke,” he said.

The assumption that he was a drug abuser, presumably because he was Black, “angered me,” he said. “But it also made me realize that … you can’t look at somebody and tell if they have sickle cell.”

Sickle cell patients and their advocates often feel unseen as they work to educate both the public and the medical community itself about the disease.

Though sickle cell disproportionately affects Black people in the United States, millions around the world suffer from it, from sub-Saharan Africa to Saudi Arabia, India and Mediterranean countries such as Italy.

In this country sickle cell patients are a relatively small band of “warriors”—the word often used to describe them. About 100,000 people in the United States have the disease, including an estimated 2,000 in Missouri and about 700 Kansans.

Patients tell of receiving substandard medical care because health care professionals don’t know enough about the disease. In recent months, Wake and other advocates have succeeded in getting legislation passed in Missouri that addresses those problems, and are working to get a similar bill passed in Kansas.

“I think the general sense is people know very little about it. Or if they know anything about it they know very little about how much it can impact not just the individual, but the family too,” said Donna McCurry, a senior nurse practitioner at University Health’s Sickle Cell Center.

An especially cruel disease

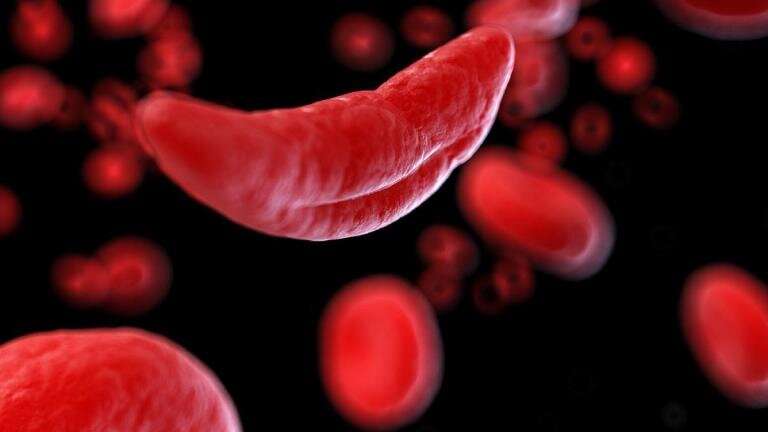

Sickle cell is inherited when a baby receives two genes—one from each parent—that genetically code for abnormal hemoglobin. It affects the red blood cells that carry oxygen to every part of the body.

The culprit hemoglobin—the protein in red blood cells that carries the oxygen—causes normally round and flexible cells that glide easily through small blood vessels to become hard, sticky and C-shaped like sickles.

They clog blood flow, and the resulting oxygen deprivation can damage organs and cause serious complications such as the strokes Wake has suffered. One permanently weakened his right hip. Now he walks with a slight limp.

But pain makes sickle cell disease especially cruel.

Patients live in constant fear of when the next pain crisis might strike. The pain can last hours, days, weeks.

When those red blood cells clump up inside his vessels, Wake feels indescribable pain. He can usually alleviate it with Extra Strength Tylenol and prescription hydrocodone. His doctor prescribed heat therapy, and he bought a hot tub. The hot water expands his blood vessels, soothing the pain.

But when the pain starts moving into his spine, it’s time to head to the hospital for IV intervention.

“Sometimes the pain is so painful for me, my eyeballs hurt,” said Wake. “It’s a pain that once it manifests and presents itself, it’s excruciating.

“Sometimes you are beside yourself, you just don’t know what to do.”

One of the first sickle cell patients ever studied in the late 1960s considered jumping off a bridge as a teenager before his mother stopped him.

“If you can imagine having a baby that hurts so bad that even touching it will make it cry,” said McCurry. “And this is from the time they are born and it does not get better.”

Wake was one of three sons born to Virginia and Lee Wake on a dairy farm in Leavenworth, 30-some miles north of Kansas City. All three sons came into this world with sickle cell.

Two have died.

Wake’s older brother, David, succumbed at age 2 1/2. His shocking death, and an autopsy that found sickle cell, led to Kevin being tested two days later.

His younger brother, John, died of complications of the disease in 2003. He was 32.

“I feel like I’ve been cheated by not having an older brother,” said Wake. “I don’t remember David. I only see him in pictures.”

‘You’d be wasting your time’

He still carries anger over how David died. His older brother, as a baby and toddler, was prone to colds, fevers and infections.

Wake’s mother had read about sickle cell and asked the family pediatrician in Leavenworth if David should be tested.

“He laughed at my mom and told her, ‘You don’t have sickle cell, your husband doesn’t have sickle cell, you’d be wasting your time,'” Wake said. The doctor didn’t consider that the parents might be carrying this recessive gene.

So his mother, trained in a day when nurses did not second-guess doctors, let it go. But David got sicker. And ultimately, his little heart ruptured, Wake said, before he could be seen by a specialist.

“My mom has always felt guilty that she didn’t act on her intuition,” Wake said. “I see it as a hurtful event, but I also see it as a blessing, that his death led to my diagnosis and then John’s diagnosis later. And my mom became a very strong advocate for us.”

Wake worked in pharmaceutical sales for 23 years until the disease forced him into medical retirement after the second stroke in 2017.

Advocacy is his new job. He is president of the Uriel E. Owens Sickle Cell Disease Association for the Midwest, which has supported patients in the Kansas City area for more than 40 years.

In recent months Wake has testified in Jefferson City and Topeka for sickle cell legislation. Last year he helped push through Missouri legislation that established a statewide Sickle Cell Awareness Week in September.

It also requires the state’s rare disease advisory council to annually review available treatments and how providers are being taught about sickle cell.

In Topeka, Wake has argued for a bill that would designate an awareness week in Kansas and require the state health department to study and report on topics related to the disease. A House committee passed the bill last month.

‘Contributing members of society’

Last year, Wake starred in a video about sickle cell disease produced by Pfizer pharmaceutical company. “Kevin’s Story” showed him as a husband, dog owner, volunteer and caregiver for his parents. His mother died in January.

“I would like people to know that patients with sickle cell are still human beings and they have a disease that causes a lot of pain,” he told The Star.

“It’s a diagnosis, it’s not a definition of who they are and what they can do. People living with sickle cell can still be contributing members of society.”

But not many people have to go to the lengths Wake does to be that contributing member of society.

Every six weeks, like clockwork, you’ll find him tethered to a machine at the Sickle Cell Clinic at University Health, getting a blood transfusion. He’s gotten transfusions since 2017. He calls it an “oil change.”

During the procedure his abnormal red blood cells are filtered out while seven units of “good,” fresh, donated blood from the Community Blood Center flow slowly into his body through a permanent port in his chest.

The transfusions “hopefully prevent me from having strokes,” he said

As a one-stop shop devoted to sickle cell disease, the center is unique in Kansas City.

Patients asked for a place devoted solely to their needs. Much of the staff has been there for years, so they know patients, their families and medical histories well, said McCurry, whose specialty is family practice. They also see the psychological damage of sickle cell.

Because patients “look fine on the outside,” McCurry said, some of their own families doubt them when they say they are in pain.

That suspicion forces a lot of patients to “fake being well,” she said.

The clinic participates in a project sponsored by the Health Resources and Services Administration, known as HERSA. The federal agency is tasked with improving access to health care for people who are uninsured or medically vulnerable.

The clinic is also participating in research by Johns Hopkins University, which runs an infusion center that is a model for others across the country.

Stigma is one of the biggest challenges in that care, McCurry said.

“Some of it is based on the fact that most sickle cell patients, at least in the U.S., are Black. And you come in asking for pain medication,” she said. “There is this unconscious bias about Black people who want pain medication.

“There is a lot going on in the advocacy world trying to change that stigma.”

She encourages patients at the clinic to keep their medical records, and a list of their medications, with them at all times. That information can be kept on cellphones now.

Wake does that. He also wears a red rubber bracelet around his wrist.

It says, “Break the sickle cycle.”

2023 The Kansas City Star.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Source: Read Full Article