As the 988 crisis line debuts across the United States, a new Harris Poll shows that Americans are ready to make mental health and suicide prevention a top priority.

Over eight in 10 adults now believe it’s more important than ever to consider suicide prevention a national public health crisis, according to the poll sponsored by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

Unfortunately, the poll also revealed some major misconceptions about how the 988 line actually works, as well as potential barriers that could keep people from reaching out for the help they need.

The good news? Nearly everyone who responded to the poll (94%) sees suicide as a preventable public health issue.

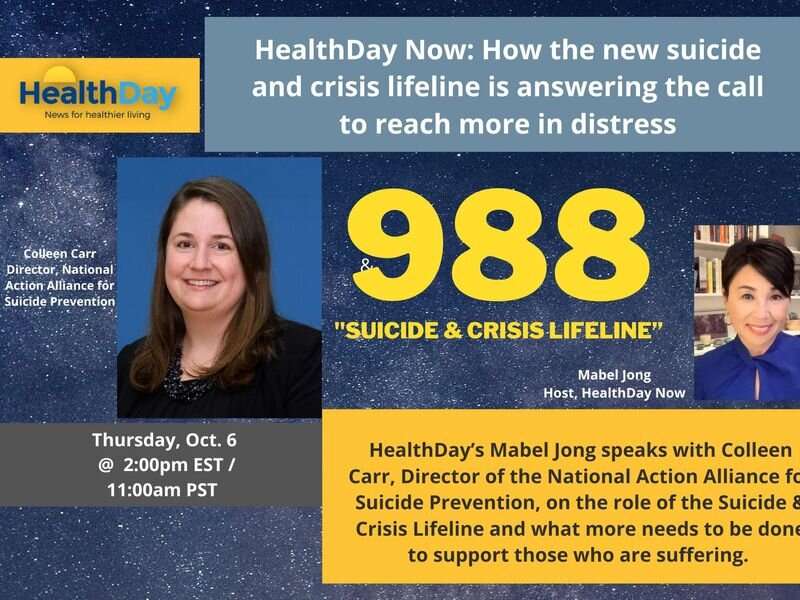

“More people during the pandemic talked about mental health. In the early days of the pandemic, we frequently saw mental health as the headline in newspapers,” said Colleen Carr, director of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (NAASP). “Ten years ago, I don’t think we would have seen mental health front and center at the beginning of a global pandemic, and we really did see that this time.”

The successful launch this summer of the 988 crisis line reflects this new emphasis on mental health.

Nearly three in five Americans are familiar with 988, even though it’s only been in place for two and a half months, the poll found.

“I thought it was very interesting that even though 988 only came out in July, already more than half of people have heard of it,” said Jill Harkavy-Friedman, senior vice president of research for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. “The effort to get that information out has been successful. I’m hopeful that people will know the number is there and will use it if they need it, whether for themselves or somebody else.”

In fact, nearly three out of four people would be comfortable contacting a crisis line to help either themselves or someone they know, according to the poll.

Cal Beyer, a member of NAASP’s executive committee and vice president of workforce risk and worker well-being at Holmes Murphy and Associates in Iowa, knows about both kinds of crisis calls, first having dialed a suicide hotline back when he was a teen in crisis. Since then, the 61-year-old Seattle resident has become a staunch advocate for suicide prevention, reaching out for help not only when he needs it, but also helping others make the call.

“I grew up in a family of five children. My parents sat me down when I was 12, let me know that mental health challenges ran on both sides of the family tree, to not be embarrassed,” Beyer said during a HealthDay Now interview.

“I shared with my parents a couple years later that I was going through some tough times… in the end, my mom gave me contact information for a hotline in my hometown of Madison, Wisc. I believe I was 14 or 15,” Beyer said. “The first time I made that telephone call, I didn’t talk about it a whole lot. But it was life-changing for me and I encourage people to make those types of calls all the time,” he added.

“Don’t wait for a crisis to happen,” Beyer stressed. “Make the call when you first feel isolated, you know, rejected, alone. Don’t wait for a crisis. Reach out. It’s a lifeline. It is hope. It is help.”

Despite growing awareness that suicide and mental health issues have become pressing, there are still issues in addressing suicide and mental health crises, the poll showed.

The 988 crisis line is anonymous, and 98% of the time “that call to a trained counselor is the intervention. That’s the support they need,” Carr noted. “It’s fewer than 2% of calls to the Lifeline network that require connection to emergency services.”

However, two-thirds of people polled said that if they call a crisis line they would expect police (64%) or emergency medical services (66%) to show up at their door.

The concern is that some groups—Black Americans, for example—might be hesitant to call a crisis line if they expect a police response.

“We need to help people understand that it is unusual for a person to show up,” Harkavy-Friedman said. “The idea of a crisis line is to help de-escalate the crisis so that you can get help or so the people around you could help you get help. It’s very unusual for the police to be called in. Keep in mind, they don’t even know who you are or where you are unless you tell them.”

Carr noted that “it’s important to recognize that part of the value of our crisis call center network across the country is that it really is a place where people are connecting with a trained counselor who is providing the support that they need in the moment.”

Making sure that every American has at least some training to respond to a cry for help is another top concern for suicide prevention experts.

Most people coping with suicide would turn to a trained professional for help—most often either a mental health provider (56%), a family doctor (43%) or a crisis line (38%), the poll found.

But the poll also found that those in crisis would also consider reaching out to a wide variety of others.

Nearly one-quarter said they would trust a faith leader, a spouse or significant other or a friend, while 7% said they’d talk to a coworker.

Most Americans want to help, but many don’t know how

“That’s really important to know, that we all can play a role in suicide prevention,” Harkavy-Friedman said. “It doesn’t mean you have to become a therapist, but it does mean that if somebody connects with you and says that they or someone they know is thinking about suicide, we all have to learn what to do and where to go to help that person—because people will show up.”

People do seem to understand there’s a knowledge gap there, the poll found.

Three-quarters of the poll participants believed that most people show signs before suicide, but only one in three felt they personally could tell when someone is considering suicide. And nearly four out of five believed that training and education for professionals would be the most helpful for reducing the number of people who die by suicide.

The heartening news is that most people do want to help those in need around them. About 83% said they would be interested in learning how they might be able to play a role in helping someone who is suicidal, the poll found.

“The vast majority of people would want to do something to help someone else,” Harkavy-Friedman said. “People are learning that if you’re worried about someone you can call 988, either with them in the room or without, to find out what to do so that you can help them.”

The U.S. health care system and its lack of emphasis on mental health is another barrier to good mental health care, the poll found.

Carr said that “about 92% reported that they value mental health as much as or more than physical health, but 51% still feel that physical health is treated as more important than mental health by our health care system.”

People are also concerned about being able to find or afford the help they need.

Nearly half of U.S. adults said that inability to afford treatment keeps people who are thinking about suicide from seeking help. Another 44% are worried about being able to access treatment.

That’s where the 988 line can play an immediate role, said Kim Torguson, the NAASP’s director of engagement and communications.

“One of the main reasons we wanted to make it a three-digit number is we wanted to make it easy, much more accessible, confidential and free of charge,” Torguson said. “It’s important to reinforce that while we have to address these other shortages and issues, we do have a line that is accessible and affordable for those who are struggling.”

Overall, Carr noted, the poll results show that “the public is ready and hungry for a comprehensive response” to suicide and mental health crises.

“I think that’s a really great place to be, and it’s incumbent on all of us to make sure that the moment is not lost and that real, tangible change is made, so five years from now we’re not talking about the same systemic barriers to accessing care,” she added.

Source: Read Full Article