The net cost of prescription drugs—meaning sticker price minus manufacturer discounts—rose over three times faster than the rate of inflation over the course of a decade, according to a study published today in JAMA. It’s the first analysis to report trends in net drug costs for all brand-name drugs in the U.S.

The study is one of three manuscripts by researchers in the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing (CP3) at the University of Pittsburgh’s Health Policy Institute published in this week’s special issue of the journal, which focuses on prescription drug costs.

“Previously, we were limited to studying list prices, which do not account for manufacturer discounts. List prices are very important, but they are not the full story,” said lead author Inmaculada Hernandez, Pharm.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of pharmacy at Pitt. “This is the first time we’ve been able to account for discounts and report trends in net prices for most brand name drugs in the U.S.”

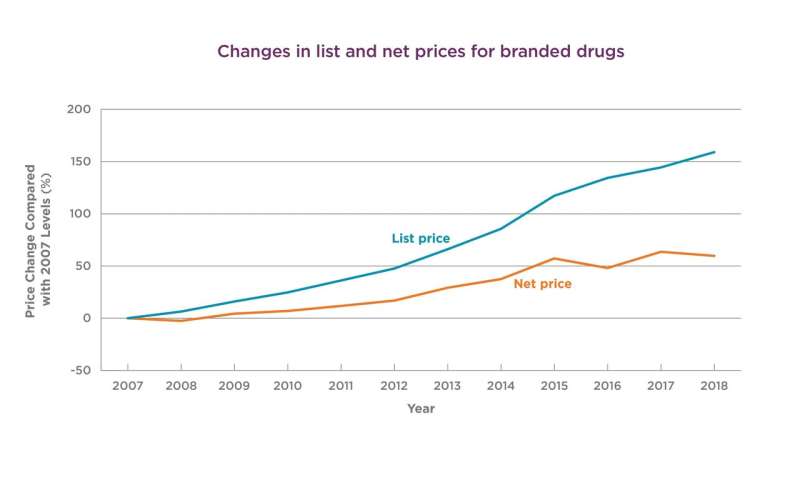

Hernandez and colleagues showed in past research that list prices for prescription drugs have increased steadily over the past decade.

In the new analysis, the team used revenue and usage data for 602 brand-name drugs to track list and net prices from 2007 to 2018. Inflation-adjusted list prices increased by 159%. Net prices, which account for rising manufacturer discounts, including rebates, coupon cards and 340B discounts, increased by 60%. That’s 3.5 times general inflation.

In 2015, net prices began leveling off. Still, the authors caution that stable net prices don’t automatically mean that prescription drug costs are affordable for consumers.

“Net prices are not necessarily what patients pay,” said senior author Walid Gellad, M.D., M.P.H., associate professor of medicine and health policy at Pitt and director of the CP3. “A lot of the discount is not going to the patient.”

That’s because the vast majority of the discount likely consists of rebates paid directly to public and private insurers. Rebates don’t usually affect the amount patients pay through copays or coinsurance, which are based on list price, not net.

Beneath the overall trends, there was large variability across different drug classes. In some cases, such as insulins or TNF inhibitors, there was a widening gap between list and net prices. In others, such as cancer drugs, list and net prices increased in parallel. Multiple sclerosis treatments were an exceptional case, where even after discounts, net prices more than doubled over the decade in inflation-adjusted dollars.

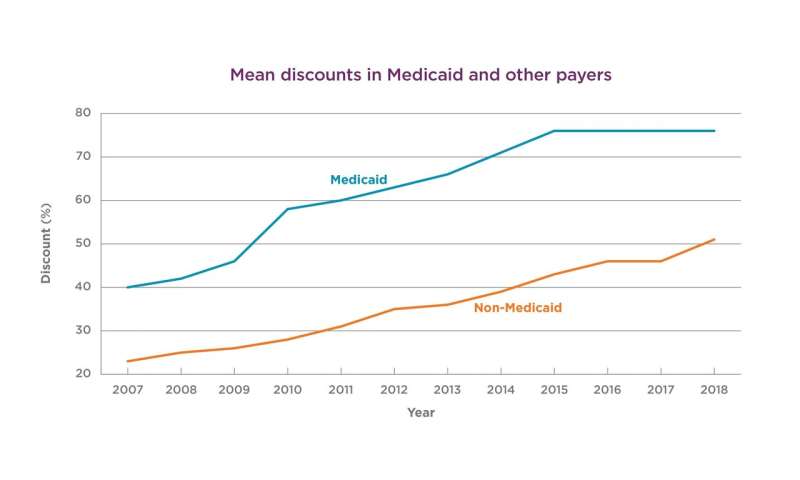

The study also shows that discounts are much larger for Medicaid than for other payers, likely reflecting regulation, including the mandatory Medicaid rebate based on price increases over inflation. Discounts for other payers are based on negotiations.

The Senate Finance Committee is considering a bill that would add price inflation-based rebates to Medicare, similar to Medicaid.

Source: Read Full Article