Ever wondered why your voice sounds different in a recording compared to how you perceive it as you speak? You are not alone. The reason has to do with the two different types of transmission of our own voice, namely, air-conducted (AC) speech and bone-conducted (BC) speech. In the case of AC speech, the voice is transmitted through the air via lip radiation and diffraction, whereas for BC speech, it is transmitted through the soft tissue and the skull bone. This is why when we hear ourselves in a recording, we only perceive the AC speech, but while speaking, we hear both the AC and the BC speech. In order to understand, then, the relationship between speech production and perception, both these speech transmission processes need to be accounted for.

This has been further corroborated by recent scientific investigations which show that BC speech transmission affects the perception of our own voice similarly to AC speech transmission. However, the transmission process of BC speech remains to be understood accurately.

In a new study published in Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, a team of scientists from Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST) attempted to understand the BC speech transmission process by studying the vibrations of the regio temporalis (or RT, the temple region of the head) and the sound radiation in the ear canal (EC) caused by sound pressure in the oral cavity (OC). Professor Masashi Unoki of JAIST, who was involved in the study, outlines their approach, “We assumed a transmission pathway model for BC speech in which sound pressure in the OC is assumed to cause vibration of the soft tissue and the skull bone to reach the outer ear. Based on this assumption, we focused on how excitations in the OC would affect the BC transmission to the RT and the EC.”

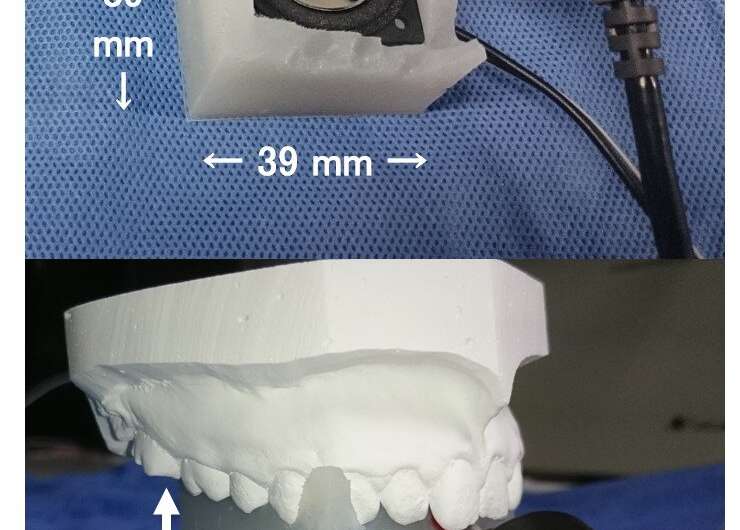

For measuring BC transmission, the scientists selected five university students (three men and two women) aged 23–27 years with normal hearing and speaking ability. In each participant, they fitted a small loudspeaker to their hard palate (the structure that sits at the front of the roof of the mouth) and then transmitted computer-generated excitation signals to them. The response signals were simultaneously recorded on the skin in their left RTs and right ECs with a BC microphone and a probe microphone, respectively. Each participant underwent 10 measurement trials.

The team found, upon analyzing the transfer function (which models the frequency response of a system), that the RT vibrations support all frequencies up to 1 KHz while the EC pressure accentuates frequencies in the 2–3 KHz range. Combining this observation with an earlier report which showed that BC speech is perceived to be “low pitch,” or dominated by low frequencies, the team concluded that the EC transmission, which cuts off both very low and very high frequencies, does not play a major role in BC speech perception.

Source: Read Full Article