A tropical disease once seen almost exclusively in returning travelers is now being detected in Texas and the South in people with no international travel history—caused by a parasite strain that’s different from the imported cases, new evidence suggests.

An analysis from researchers at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention presented Oct. 19 at the annual meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene emerged from a curious rise of domestic infections over the last 10 years from a disfiguring skin disease called cutaneous leishmaniasis. It’s caused by a parasite spread by bites from a sand fly.

While most of the U.S. cases were in patients who had traveled to countries where leishmaniasis is common, there were 86 patients with no travel history. Using genetic sequencing, CDC scientists found that a strain of the Leishmania mexicana parasite infecting non-travelers had a distinct genetic fingerprint, suggesting infections were caused by a uniquely American genotype of the disease that was spread by local sandfly populations.

This is evidence of local transmission—that leishmaniasis may be well-established in some parts of the United States, said Dr. Mary Kamb with the Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria at the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infections, in a news release.

“While most of these infections were in people living in Texas, sand flies that can transmit leishmaniasis are found in many parts of the country and especially in the southern United States,” Kamb said.

In Texas, there is growing awareness of leishmaniasis as a potential diagnosis for skin lesions, due to a history of cases in people returning from Mexico and increasing recognition of the possibility of locally acquired cases, according to Kamb. In fact, cutaneous leishmaniasis is a reportable condition in the state.

The increasing number of cases could be caused by a number of factors, including changes in climate conditions that may lead to suitable environments for sand fly survival and reproduction, enabling the transmission of leishmaniasis in new areas, said Vitaliano Cama, a senior advisor with CDC’s Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria. By linking domestic infections with a distinct strain, it may be easier to detect the emergence of locally acquired cases in new areas, the CDC team says.

With the CDC study revealing DNA evidence of a locally acquired strain of cutaneous leishmaniasis, there are concerns domestic sand flies could acquire a deadly form of the disease via dog imports.

What is leishmainiasis?

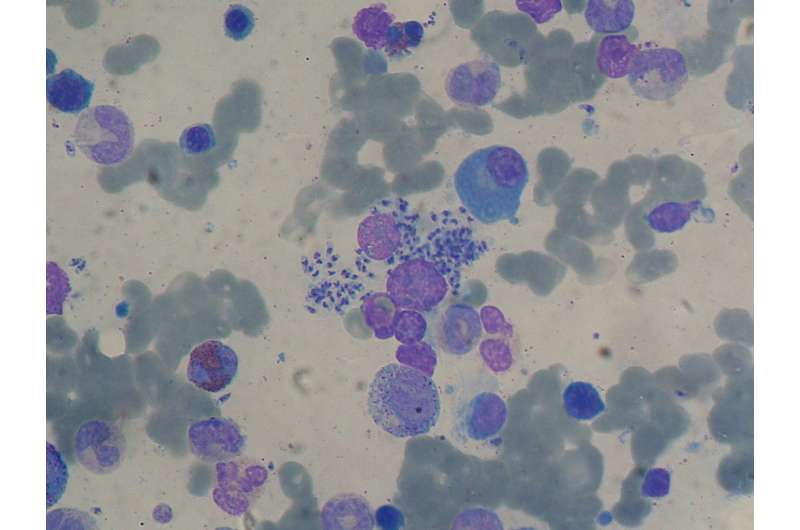

Cutaneous leishmaniasis, the most common form of leishmaniasis affecting humans, is a skin infection caused by a single-celled parasite that is transmitted by the bite of a sandfly. There are about twenty species of Leishmania parasites that can cause cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis infections produce skin ulcers that can take weeks or months to emerge post-exposure. While there are medications to treat infections, the disease can cause disfiguring scars if allowed to progress.

According to the World Health Organization, cutaneous leishmaniasis infects up to one million people annually, mainly in the Middle East, central Asia, northern Africa and especially Latin America.

Will a more serious form of leishmaniasis become endemic?

Growing evidence of cutaneious leishmaniasis circulating in U.S. sand fly populations is increasing concerns that a life-threatening form of the disease, visceral leishmaniasis, could also gain a foothold in domestic sand flies—by feeding on imported dogs that are carrying the pathogen.

Dogs, the primary host for this disease, are now regularly coming into the U.S. having lived in areas where Leishmania parasites circulate in animals and people. Domestic sand fly populations could acquire visceral leishmaniasis parasites from the growing number of dogs coming into the country from regions where the disease is common, another study featured at the ASTMH annual meeting found.

Domestic dog imports from abroad, for breeding or via dog rescue organizations, have jumped sharply, the authors said. About a million dogs enter the United States every year, most without receiving proper screening for infectious diseases. The study authors say the United States needs a better system for guarding U.S. sand fly populations against Leishmania infantum, one of the world’s deadliest tropical parasites.

While visceral leishmaniasis also is transmitted by sand fly bites, it’s caused by a different but related parasite called Leishmania infantum. It affects internal organs and kills between 20,000 and 30,000 people worldwide each year.

There are no drugs to prevent the disease, though there are vaccines available in Europe and Brazil for dogs. There are medications for treating infections in people, though some can cause serious side effects.

Infected dogs can be treated with medications that reduce the number of parasites they carry, which lowers the risk that they will transmit parasites when bitten by sand flies. Most infected dogs will relapse, requiring regular screening and treatment as well as topical insecticide to prevent spread to other dogs or people.

“Both forms of leishmaniasis cause tremendous suffering around the world and the fact that they now pose risks in the United States shows why we need to work together as a global community to fight infectious diseases wherever they exist,” said Dr. Daniel Bausch, ASTMH president, in a statement.

“A global approach is especially important since climate change allows insects that carry pathogens like Leishmania, dengue virus and malaria to expand their range.”

2023 Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Source: Read Full Article