Introduction

Dietary changes and the GMB

Probiotics and the microbiome

Dietary patterns and the GMB

Conclusions

References

Further reading

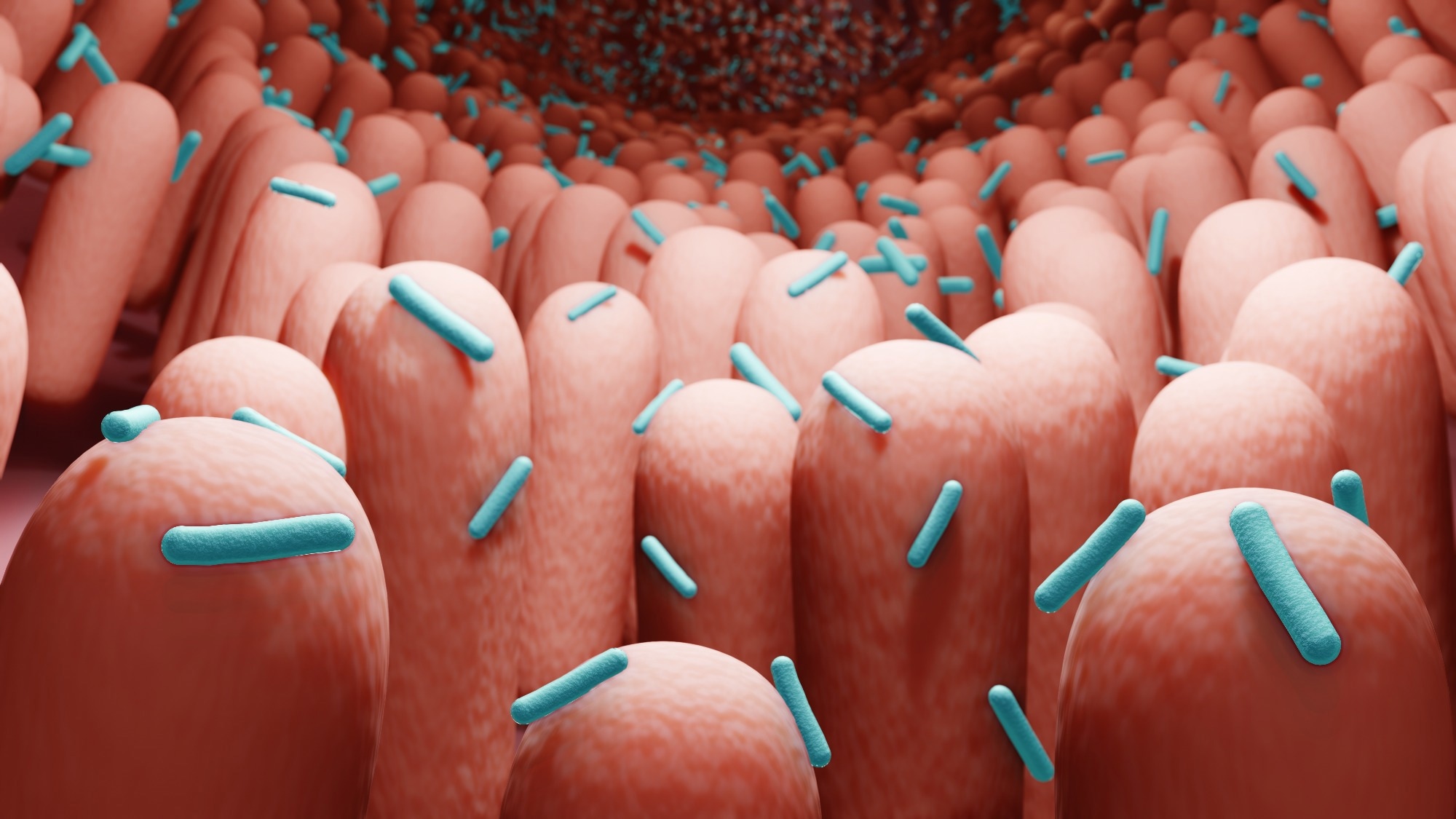

The gut microbiome comprises all the genes contained in the 100 trillion microbes that inhabit the surface of the human digestive system. These are mostly commensals, with some potential or opportunistic pathogens.

Image Credit: ART-ur/Shutterstock

Image Credit: ART-ur/Shutterstock

The diet plays a huge role in the composition of the microbiome, which varies considerably between vegetarian and mostly meat-eating communities and individuals. The Westernized diet causes a shift in the gut microbiome (GMB) profile from that found in agrarian communities in Africa, for instance.

Such changes lead to changes in host metabolism and immune response pathways, which eventually affect human health. The GMB is known to be involved in the pathogenesis of multiple disease conditions, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer, besides inflammatory bowel disease.

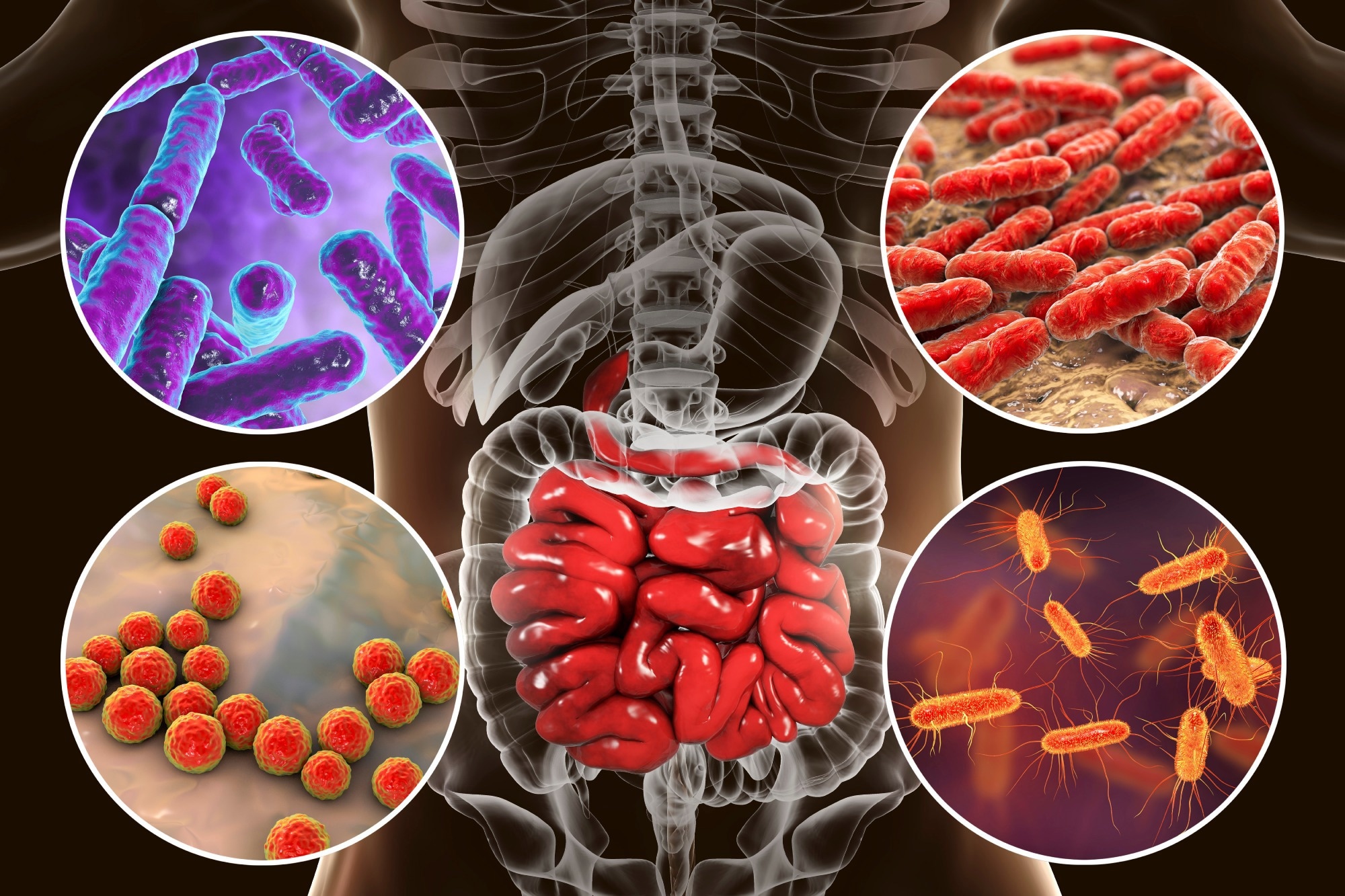

The human GMB is dominated by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. The former are gram-positive, and the latter gram-negative. There are various enterotypes, or categories of microbiota, each of which is enriched for specific bacterial genera. These are determined based upon the ratio of certain genera or the relative abundance of beneficial bacteria to facultative anerobes.

The three enterotypes are characterized by:

- High Bacteroides-to-Prevotella ratio – Western diet

- High Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio – plant-based diet

- Small increase in Firmicutes, specifically Ruminococcus – prolonged fruit and vegetable consumption, increased in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Some important GMB functions include the biosynthesis of vitamins and essential amino acids, and key metabolites from undigested human dietary factors. These include short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, butyrate and propionate that are key energy sources for the intestinal epithelium, preserving the mucosal barrier.

The GMB also promotes local immunity at the gut mucosa, via their interactions with Toll-like receptors (TLRs), T cells, antigen presenting cells and lymphoid follicles. They also stimulate the production of CD4 T cells in the spleen and enhance the production of systemic antibodies.

Dietary changes and the GMB

A major change in diet leads to a large alteration in the composition of the GMB within just a day. Once the new diet is stopped, however, the pattern reverts within 48 hours.

Increased fat or sugars in the diet tend to disrupt the circadian rhythms. Again, severe systemic inflammation or stress could lead to acute changes within 24 hours.

In the long-term, immigrants to the USA develop a fourfold higher obesity risk, associated with a reduction in the ratio of Prevotella (fiber-degrading) to Bacteroides by factors of 10. This change is in direct proportion to the duration since immigration.

Image Credit: Victoria Sergeeva/Shutterstock

Image Credit: Victoria Sergeeva/Shutterstock

Protein and the GMB

Increased protein consumption is associated with higher microbial diversity. The consumption of vegetable and light animal protein, such as in legumes and whey, leads to an increase in commensals like Bifidobacterium (butyrate-producing) and Lactobacillus. In addition, whey reduces pathogens like Bacteroides fragilis and Clostridium perfringens, while legumes foster SCFA production.

With high amounts of beef or other animal protein in the diet, the GMB is enriched in anerobic bacteria such as Bacteroides, Alistipes, Bilophila and Clostridia, but lower Bifidobacterium adolescentis, compared to strict vegetarians.

With a high-protein low-carbohydrate diet, Roseburia and Eubacterium rectale are low. Low E. rectale has been found in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). These findings may explain the association of animal protein consumption in larger amounts with an increased risk of IBD.

CVD risk is also increased by the atherogenic molecule trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), which is correlated with several types of bacteria found at high levels in meat-eaters.

Fats and the microbiome

Western diets are typically high in saturated and trans fats, but heart-healthy diets are low in both, while containing mono- and polyunsaturated fats. High dietary fat content is linked to a greater abundance of anerobes and Bacteroides, Clostridiales, and Enterobacteriales, leading to more propionate and acetate production, but less Lactobacillus intestinalis. The latter is negatively associated with weight gain in rats.

Saturated fats are associated with a higher abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Conversely, a low-fat diet increases Bifidobacterium abundance, causing lower fasting glucose and total cholesterol levels. These fat-related changes are also linked to metabolic inflammation, and insulin sensitivity.

Carbohydrates and microbiota

Digestible sugars and starches break down under enzyme action in the small gut, raising the blood glucose level and thus increasing insulin release. Dates, which are rich in glucose, fructose, and sucrose, increase the proportion of Bifidobacteria, but reduce that of Bacteroides. Lactose addition also causes a fall in Clostridia with an increase in SCFAs.

High-carb diets are associated with an increase in the yeast Candida albicans, and the methanogen Methanobrevibacter. Abstinence from dairy, alcohol, cured and fatty meats, and simple starches and sugars, led to a cure of Candida overgrowth in 85% of patients treated with nystatin, but only 42% with nystatin alone.

Lactose is thus beneficial in its effects on the GMB. In contrast, artificial sweeteners provoke glucose intolerance more than natural sugars, namely, glucose and sucrose, via intestinal dysbiosis, thus raising questions about their use.

Omics eBook

The FODMAP (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) diet has been suggested to help improve the GMB and alleviate IBS symptoms. It is difficult to sustain over the long term due to the rigid restrictions on multiple plant-based foods. Conversely, the specific carbohydrate diet (SCD) has been around for over a hundred years.

Indigestible carbohydrates, found in soybeans, whole wheat and raw oats, and non-digestible oligosaccharides (galactooligosaccharides (GOS), fructooligosaccharides (FOS), and inulin), are commonly called dietary fiber and resistant starch. These provide “microbiota accessible carbohydrates” (MACs). These are fermented by gut microbes (LAB and Bifidobacterium) in the colon, yielding energy and carbon sources, including SCFAs, to the human host.

The increased SCFAs and better gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) activation by the fermentation products may act via SCFA receptors and other pathways to favorably affect the gut environment. These may thus be considered prebiotics.

Such changes are linked to metabolic and immune restoration, with lower inflammatory markers, improvement in insulin sensitivity and normalization of glucose levels after feeding. Body mass as well as serum lipids are also reduced, along with anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer effects on the colon.

Probiotics and the microbiome

Microbes that can be ingested to improve gut health and prevent or treat IBD are often found in fermented foods like yogurt and cultured milk and are called probiotics. These microbes affect the GMB to modulate inflammation. Notably, they bring about an increase in Bifidobacteria and/or Lactobacilli, with reductions in coliforms and total, very low density and low-density cholesterol.

Simultaneously, they are linked to better insulin sensitivity. GI intolerance is alleviated by such products, with higher serum IgA levels indicating a stronger antibody response. Moreover, Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria are used to prevent traveler’s diarrhea.

Polyphenols and the GMB

Fruits, tea, cocoa products, and wine contain high polyphenol concentrations, which may help to increase beneficial microbes. They have immunomodulatory, anticancer and anti-inflammatory effects. Some of these compounds are antibacterial as well, acting against Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella typhimurium, and pathogen Clostridia.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock

Dietary patterns and the GMB

Westernized diets are typically antagonistic to a healthy GMB, being associated with reductions in Bifidobacterium and Eubacterium, but increases in E. coli and Enterobacteriaceae. Conversely, plant-based diets, whether vegan or vegetarian, promote Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides species.

The Mediterranean diet has a beneficial fatty acid profile, due to its composition rich in whole grains and legumes, nuts, fruits and vegetables, seafood, poultry, olive oil, and wine, and little red or processed meat, sweets, and dairy products. It is correlated with increases in SCFAs and higher levels of beneficial LAB, Bifidobacterium, Prevotella and Firmicutes, with reductions in Clostridia.

The keto diet has shown preliminary promise in the treatment of refractory epilepsy and other neurological conditions, linked to the changes it induces in the GMB.

On average, twenty five percent of plasma metabolites are different between omnivores and vegans, suggesting a significant direct effect of diet on the host metabolome.”

The diet thus alters the gut-brain interactions via neuroendocrine and neurotransmitter modulation. For instance, LAB and Bifidobacteria convert glutamate, an amino acid, into the important neurotransmitter GABA, which is involved in mood stabilization. GMB restoration has resulted in some cognitive improvement therapy in animal models.

Conclusions

Human health depends heavily on the gut microbiota. Intestinal dysbiosis has been implicated in multiple disorders, including obesity, autoimmune and mental health disorders.

The GMB modulates the immune response, dampening inflammation via humoral and cellular pathways. The SCFAs produced by these microbes have multiple activities, including anti-allergic airway effects. In addition to these transcriptional and direct actions, epigenetic modifications also arise from GMB activity, bringing about healthy immune responses.

The gut microbiota also affect metabolic health, as indicated by the aberrant ratios of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes in obesity. This is restored by reducing the intake of calories.

Such a GMB also puts the host at high CVD risk. LAB and others are linked to better responses to dietary interventions in obesity, perhaps via the differences in fatty acid breakdown caused by the changes in the gut microbiome.

Probiotics and fecal microbiota transplant are examples of current interventions aimed at a variety of disease conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), ulcerative colitis, Clostridium difficile-associated colitis and obesity.

GMB changes after such interventions are personalized, depending on the baseline profile, individual metabolism, and thus the genotype and epigenetics. Precision medicine could benefit greatly from studies that explore these linkages.

References

- Singh, R. K. et al. (2017). Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. Journal of Translational Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1186%2Fs12967-017-1175-y. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5385025/

- Leeming, E. R. et al. (2019). Effect of diet on the gut microbiota: rethinking intervention duration. Nutrients. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fnu11122862. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6950569/.

- Mayer, J. H. et al. (2022). Role of diet and its effects on the gut microbiome in the pathophysiology of mental disorders. Translational Psychiatry. DOIhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-01922-0. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-022-01922-0.

- Tomova, A. et al. (2019). The effects of vegetarian and vegan diets on gut microbiota. Frontiers in Nutrition. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2019.00047. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2019.00047/full.

- Hills Jr., R. D. et al. (2022). Gut microbiome: profound implications for diet and disease. Kompass Nutrition & Dietetics. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000523712. https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/523712.

Further Reading

- All Microbiome Content

- What is the Human Virome?

- How Does the Diet Impact Microbiota?

- The Microbiome of a Newborn

- Fecal Microbiota Transplant

Last Updated: Mar 14, 2023

Written by

Dr. Liji Thomas

Dr. Liji Thomas is an OB-GYN, who graduated from the Government Medical College, University of Calicut, Kerala, in 2001. Liji practiced as a full-time consultant in obstetrics/gynecology in a private hospital for a few years following her graduation. She has counseled hundreds of patients facing issues from pregnancy-related problems and infertility, and has been in charge of over 2,000 deliveries, striving always to achieve a normal delivery rather than operative.

Source: Read Full Article