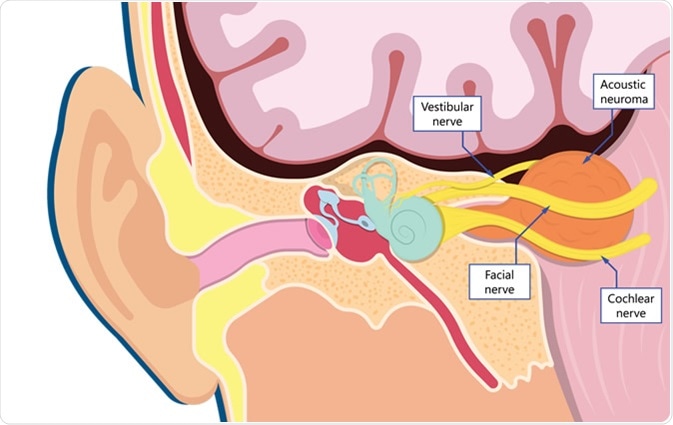

A vestibular schwannoma is a slow-growing, benign tumor developing in the nerves that connect the inner ear to the brain. These tumors are not malignant, and produce symptoms by pressure on the surrounding structures. It is called a vestibular schwannoma because it develops from the Schwann cells of the vestibular nerve. These cells produce the fatty substance called myelin which encapsulates and protects nerve fibers.

They are also called acoustic neuromas because they affect the nerve of hearing and balance.

There are two types:

- Unilateral acoustic neuromas which affect a single ear are more common, and may occur in any age group. However, people between 30 and 60 are most frequently affected. The tumor may develop because of environment-induced damage to the nerve, but the exact risk factors are unclear.

- Bilateral acoustic neuromas are rarer, are genetic in origin, and affect both ears. The underlying defect is in the gene on chromosome 22 that causes neurofibromatosis-2 (NF2). This is an autosomal dominant disorder, and the offspring of an affected parent have a 50% chance of getting this gene.

Some scientists think that both types are caused by defects in the same gene which causes Schwann cells to function. In the case of unilateral vestibular schwannomas, the mutation is acquired, whereas it is inherited in the case of bilateral tumors.

What causes vestibular schwannoma?

Vestibular schwannoma is associated with long-term exposure to noise including loud music or workplace noise. Radiation to the neck or face is also linked to vestibular schwannoma, though after many years. NF2, which may run in families, is another risk factor. In this case, symptoms of the tumor occur early in adolescence or adult life, and are usually bilateral. Other tumors of the nerves are also present.

What are the symptoms of vestibular schwannoma?

A vestibular schwannoma most commonly manifests as any of the following signs and symptoms:

- Unilateral deafness especially to high-pitched sounds

- Feeling of congestion in the ear

- Tinnitus, or ringing in the ear on the side of the neuroma

- Dizziness, and issues with keeping your balance due to the involvement of nerve fibers that help regulate the body’s balance

- Gait disturbances leading to a clumsy walk

- Tingling or numbness of the face

- Headaches and disorientation

Diagnosis of a vestibular schwannoma

The symptoms and signs must be carefully evaluated to distinguish an vestibular schwannoma from other diseases of the inner or middle ear. The symptoms are not always characteristic. Some helpful diagnostic tests include examination of the ear, hearing tests, and imaging tests.

Hearing tests or audiometry includes a test of hearing capacity, followed by a test which is sometimes used to assess the brain waves that occur when you hear specific sounds. These provide what is called a brainstem auditory evoked response and rules out deafness due to brain damage.

Computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans may be ordered to localize the tumor and assess its size. Earlier diagnosis generally makes removal easier because its size will be smaller than if diagnosis is delayed.

How is vestibular schwannoma treated?

Most vestibular schwannomas can be successfully removed, but the choice of whether to treat or not depends on tumor size, patient age and health, and the patient’s wishes. Treatment may be surgical or using radiosurgery. Very small tumors which do not appear to be enlarging may be observed with regular monitoring of the patient, as long as they do not cause any issues. The multiple tumors associated with NF2 are harder to treat.

Surgical approaches to vestibular schwannomas include craniotomies (removal of a portion of the bony skull) of several types, including a suboccipital, translabyrinthine or middle fossa entry to the brain. A keyhole approach is used for a retrosigmoid craniotomy.

When the tumor is larger, its removal may cause some damage to hearing or to the facial or trigeminal nerves that control facial function and sensation, or to balance. An alternative is radiosurgery (radiation therapy, or the “gamma knife”) which uses carefully titrated doses of radiation to debulk or remove part of the tumor and thus relieve the symptoms, though complete removal is rarely possible. Single or fractionated radiosurgery may be used. A technique called fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery (FSR) allows excellent accuracy of surgical removal while preserving hearing and facial nerve function intact.

Radiosurgery is also a good option for smaller neuromas, or for older patients. Older or sicker patients may also be treated by observation if the risks of treatment are relatively high and tumor growth slow.

Recovery after surgery for a vestibular schwannoma

Some patients will have varying degrees of deafness, leakage of the cerebrospinal fluid around the brain, facial nerve damage or other issues following surgery, and rehabilitative care may be needed following treatment to correct these issues.

Some specialized hearing aids are implanted under the skin near the ear to enhance hearing. Cochlear implants are used if the inner ear is damaged, and work by direct stimulation of the nerve from the ear. The cerebrospinal fluid leakage is typically treated by closing the tear in the brain covering called the dura through which the fluid is leaking.

Complications of vestibular schwannoma

A very large vestibular schwannoma may press against the brainstem, endangering the patient’s vital functions.

Sources

- John Hopkins. Acoustic Neuroma (Vestibular Schwannoma). www.hopkinsmedicine.org/…/vestibular-schwannoma

- Mayo Clinic. Acoustic neuroma. www.mayoclinic.org/…/syc-20356127

- NIH. Vestibular Schwannoma (Acoustic Neuroma) and Neurofibromatosis. www.nidcd.nih.gov/…/vestibular-schwannoma-acoustic-neuroma-and-neurofibromatosis

Further Reading

- All Vestibular Schwannoma Content

Last Updated: Jul 3, 2019

Written by

Dr. Liji Thomas

Dr. Liji Thomas is an OB-GYN, who graduated from the Government Medical College, University of Calicut, Kerala, in 2001. Liji practiced as a full-time consultant in obstetrics/gynecology in a private hospital for a few years following her graduation. She has counseled hundreds of patients facing issues from pregnancy-related problems and infertility, and has been in charge of over 2,000 deliveries, striving always to achieve a normal delivery rather than operative.

Source: Read Full Article