A recent study conducted by researchers at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital is the first to identify an underlying mechanism and possible drug targets for a new severe neurological disorder in children called NEDAMSS. The researchers report their findings in the journal Science Advances.

The disorder, called NEDAMSS for neurodevelopmental disorder with regression, abnormal movements, loss of speech and seizures, is caused by spontaneous mutations in the Interferon Regulatory Factor 2 Binding Protein Like (IRF2BPL) gene. In this study, the team led by Drs. Hugo Bellen, Paul Marcogliese and Debdeep Dutta at Baylor and the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute (Duncan NRI) at Texas Children’s employed fruit flies to dissect the biological function of IRF2BPL.

The team found that reducing Pits (the fly version of IRF2BPL) in neurons led to an age-dependent neurological defect in flies, which they later found was associated with an increase in the activity of the Wnt/Wingless pathway. The Wnt pathway, the human counterpart of the Wingless pathway in flies, is known to be important for the proper development and function of neurons and other organs, and its disruption results in several types of cancers.

In collaboration with Dr. Nan Cher Yeo at the University of Alabama—Birmingham and Dr. Kathrin Meyer at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, they confirmed these findings in zebrafish and in patient-derived cells as well.

In 2018, Marcogliese and Bellen, along with a team of researchers affiliated with the Undiagnosed Diseases Network—a National Institutes of Health-funded network whose goal is to find genetic variants responsible for previously unidentified disorders—discovered the NEDAMSS disorder. In collaboration with Drs. Shinya Yamamoto, Michael Wangler and others at the Duncan NRI and Baylor, as well as Drs. Loren Pena and Vandana Shashi at the UDN’s Duke clinical site, they identified mutations in IRF2BPL as the cause of severe steady regression of motor and language skills in the initial cohort of five patients.

“Today, there are 31 patients identified with mutations in IRF2BPL,” said Marcogliese, co-corresponding author of the study and postdoctoral associate in the Bellen lab. “IRF2BPL has been named as ‘one of the top 100’ autism candidate genes and its variants have been implicated in early-onset Parkinsonism. However, until now, very little was known about the biological function of this gene and how its loss results in neuronal dysfunction.”

IRF2BPL/Pits act via Wnt/Wg pathway

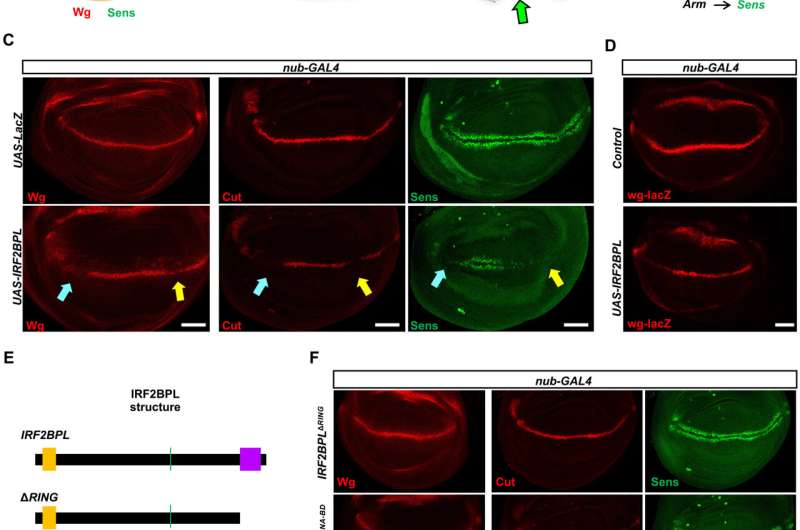

Interestingly, overexpression of Pits or human IRF2BPL in flies resulted in serrated wings and bristle loss, both of which are common when the Wnt/Wingless signaling pathway is perturbed during development.

Based on many experimental observations, the researchers concluded that Pits and Wnt/Wg act in an antagonistic manner. In agreement with these observations in animal models, they found that Wnt signaling is increased in NEDAMSS patients, whose cells are known to have reduced levels of IRF2BPL.

To understand how Pits/IRF2BPL regulates Wg/Wnt pathway, the researchers conducted biochemical assays and mass spectrometry, which revealed a Wnt antagonist, Casein kinase1 α, as one of the top binding partners of Pits. Further, they also confirmed genetic interactions between IRF2BPL and CkIα.

In summary, the study shows an antagonistic relationship between IRF2BPL/Pits and the Wnt/Wg pathway. It also shows that under normal circumstances, IRF2BPL/Pits regulates neural function by inhibiting the Wnt/Wg pathway. However, in NEDAMSS patients, with the loss of IRF2BPL, the levels of Wnt in astrocytes—a prominent type of cells in the brain—become elevated. The researchers also showed that they can suppress characteristics associated with the loss of IRF2BPL/Pits using Wnt inhibitors, which have proven to be safe and effective in treating many cancers.

Source: Read Full Article