The Ames test, also called the Salmonella test, is a short-term bacterial assay used to identify substances that cause gene mutations.

Credit: sruilk/Shutterstock.com

The basic concept of the Ames test is that a number of Salmonella strains are combined in culture that have pre-existing mutations that render them unable to synthesize histidine. The bacteria, then, require supplemental histidine in the culture media to grow and form colonies. New mutations can restore the bacteria’s ability to synthesize histidine and grow in media without it.

Importance of determining mutagenicity

Determination of mutagenicity of a chemical substance is an important part of testing and safety assessment of a substance. Handling mutagenic chemicals can pose risks to health and could lead to mutations in human ova and sperm, leading to mutations in offspring.

Mutagenic chemicals can also cause cancer. Mutations can occur as a point mutation affecting a single nucleic acid base, or as a change or rearrangement of multiple bases. Mutations can even manifest as gain or loss of an entire chromosome.

The Ames test has been recognized as a valid test of mutagenicity by government agencies and corporations and is widely used for this purpose. It is usually a preliminary screen prior to animal testing. International guidelines are in place to ensure uniformity of testing procedures for submission of data to regulatory agencies.

Ames test procedure

A number of mutations have been identified that affect the genes responsible for histidine biosynthesis in bacteria. These mutations were either spontaneous or induced by radiation or chemicals. In 1966, Ames and Whitfield developed a set of histidine mutant strains to screen chemicals for mutagenic properties.

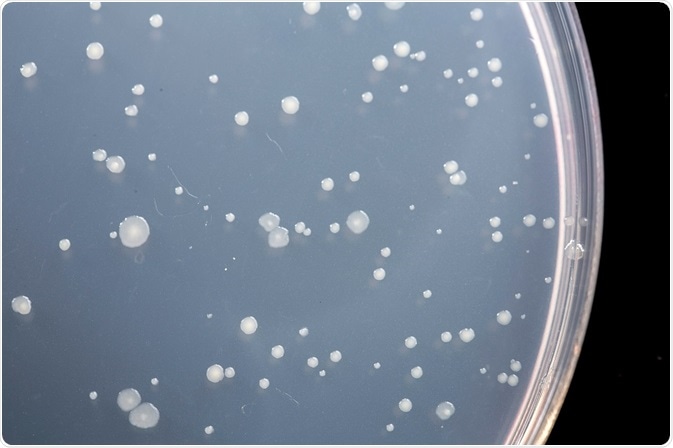

The original Ames test was a spot test carried out by applying a small amount of the test chemical to the center of an agar plate seeded with Salmonella. The chemical spot creates a concentration gradient in the circular agar plate. If the chemical is mutagenic, a ring of Salmonella colonies will form around the central spot that have reverted to wild type histidine synthesis. If the chemical is toxic, there will be a zone of zero growth.

Ames subsequently developed a plate incorporation assay with greater sensitivity and accuracy than the spot test. In the plate incorporation assay, buffer, bacteria, and test chemical are added to agar containing biotin and trace histidine. The mixture is poured on agar plates lacking histidine, and the plates are incubated upside down.

Only those bacteria that have reverted to wild type will grow on the agar plates. Trace histidine is included in the initial mixture to allow a couple of cell divisions, which is usually necessary for mutagenesis to occur. A certain number of colonies will revert spontaneously, even in the absence of a mutagenic chemical. The addition of a mutagen will increase the number of revertant colonies in a dose-dependent manner.

The plate incorporation test does not allow quantitation of the number of surviving cells. A different type of Ames test, the “treat-and-plate” procedure can provide that information. In treat-and-plate, bacteria are washed and resuspended in non-nutrient medium, and then treated with the test chemical. They are then plated on selective medium to determine mutants and on complete medium to determine survival. Mutation frequency can be calculated from the number of mutants per surviving fraction of bacteria.

Sources:

- https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4615-8966-2_9

- www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0027510700000646?via%3Dihub

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC433358/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4151811

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/768755

Further Reading

- All Biochemistry Content

- An Introduction to Enzyme Kinetics

- Chirality in Biochemistry

- L and D Isomers

- Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reaction

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019

Written by

Dr. Catherine Shaffer

Catherine Shaffer is a freelance science and health writer from Michigan. She has written for a wide variety of trade and consumer publications on life sciences topics, particularly in the area of drug discovery and development. She holds a Ph.D. in Biological Chemistry and began her career as a laboratory researcher before transitioning to science writing. She also writes and publishes fiction, and in her free time enjoys yoga, biking, and taking care of her pets.

Source: Read Full Article