New York City has authorized two safe injection sites. The sites, which officially opened in East Harlem and Washington Heights on November 30, are supervised places where people can use drugs and have access to medication that will reverse a drug overdose, if necessary.

The safe injection sites, also known as overdose prevention centers, are the first in the country, according to a media release from New York City officials. They're designed to help curb drug overdose deaths.

"New York City has led the nation's battle against COVID-19, and the fight to keep our community safe doesn't stop there. After exhaustive study, we know the right path forward to protect the most vulnerable people in our city. And we will not hesitate to take it," New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio said in a statement. "Overdose prevention centers are a safe and effective way to address the opioid crisis. I'm proud to show cities in this country that after decades of failure, a smarter approach is possible."

The move has its share of critics, and it's understandable to have questions about why a local government would allow a space where people can use illegal drugs. Here's what you need to know.

What is a safe injection site?

Safe injection sites are legally sanctioned facilities that allow people to use their own drugs under the supervision of trained staff, according to Drug Policy Alliance, a non-profit organization with a focus on reforming drug laws. You might also hear such sites referred to as overdose prevention centers, safe or supervised injection facilities, drug consumption rooms, and supervised consumption services.

"This harm reduction effort recognizes that we will not be able to effectively eliminate drug use, so reducing the risk among those who use will improve their health and welfare," Lewis Nelson, MD, chair of emergency medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, tells Health. "This is little different, in that respect, from seat belts or football helmets, although it affects a very different at-risk demographic."

There are already safe injection sites in other areas of the world, including Vancouver, Canada, and several spots in Europe. But as of now, New York City is the only city in the US with a government-sanctioned safe injection site. Although, there are plans underway in San Francisco for a safe injection site to be opened, possibly by spring 2022.

How does a safe injection site work?

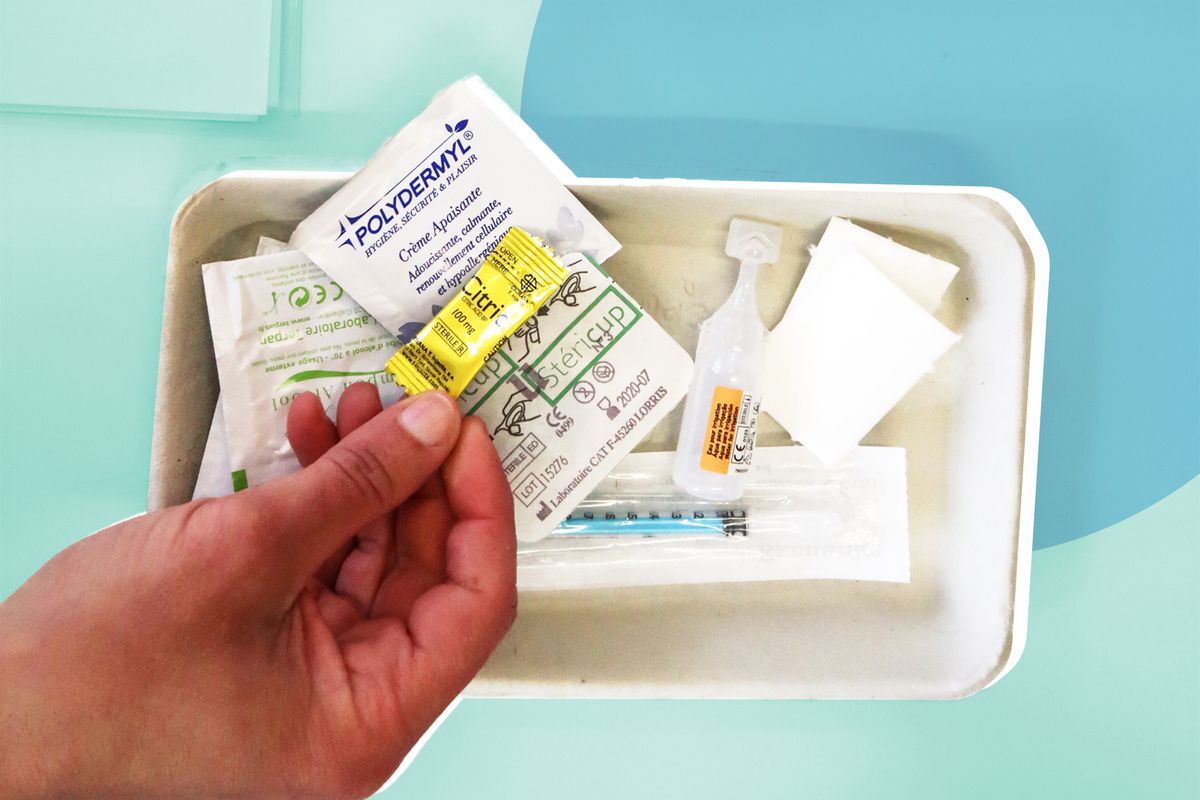

Safe injection sites do not provide drugs to people. Instead, users bring their own drugs to the site. There, staff members will not help them take or handle any drugs. But the workers are available to provide sterile injection supplies, answer questions about safe injection practices, administer first aid if it's needed, and monitor for overdoses, according to the Drug Policy Alliance.

The staff can also offer general medical advice and referrals to drug treatment, medical treatment, and social support programs.

Why do people want safe injection sites?

The main goal of safe injection sites is to help reduce drug overdoses and other health issues linked to injection drug use, Andrew Kolodny, MD, co-director of opioid policy research at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, tells Health. "If injection drug users take advantage of these sites, they can reduce the risk of overdose death, and they can reduce the risk of an injection-related infectious disease," he says. Safe injection sites can also help open the discussion about addiction treatment, Dr. Kolodny says.

"Given the increasing risks associated with opioid use due to the expansion and unpredictability of fentanyl, having a setting in which overdose can be identified and treated provides a safety net for those in this situation," Dr. Nelson says.

Dave A. Chokshi, MD, New York City's health commissioner, told the New York Times that someone dies of a drug overdose in New York City every four hours. "We feel a deep conviction and also sense of urgency in opening overdose prevention centers," he said.

A feasibility study conducted by NYC Health estimates that having four safe injection sites in the city would help save up to 130 lives a year. In their first day, staff at the sites were already able to reverse two overdoses, according to the Times. That's because staff members at safe injection sites have access to naloxone, a medicine that can help reverse an opioid overdose if it's administered quickly after someone starts to show signs of distress, Dr. Kolodny says.

One of Canada's safe injection sites reports that its facility has intervened in 6,440 overdoses since the site opened in 2003 and that there have been no overdose deaths.

Safe injection sites can do more than provide aid relating to drug use. As O. Trent Hall, DO, an addiction medicine specialist and researcher in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, points out, many people who use substances are from vulnerable populations. "Safe sites can serve as a point of contact for vital social services like housing, food, and resources for individual hoping to escape human trafficking," he tells Health. "So, the purpose of a safe site goes well beyond preventing overdose and other complications of substance use."

What’s the controversy with safe injection sites?

Not everyone is onboard with the idea of safe injection sites. "The argument against a safe injection site—putting aside the legal questions—is the concern some might have that these facilities would condone drug use," Dr. Kolodny says. "Similar concerns have been raised about syringe exchange programs, that it could result in more people starting to use drugs."

But Dr. Kolodny says the concerns are "not valid," adding, "someone is not going to decide to become a heroin user because a safe injection facility opened up in their city."

The idea of harm reduction "is often confused with the enabling of drug use," Dr. Nelson says. "Some see drug use as a moral failing and by providing access, needles, and a low-risk environment, we are fostering continued use," he continues. There are also concerns about how these facilities will impact surrounding neighborhoods. "Whether that leads to positive or adverse social consequences is undefined," Dr. Nelson says.

If injection drug users actually use these safe sites, "we can reduce overdose deaths and HIV and hepatitis infections, as well as link people to treatment," Dr. Kolodny says. "These can play an important role in overall public health."

A review of 75 studies published in 2014 did find that the sites reduce overdose deaths, lower outdoor drug use, and don't seem to increase crime or drug use. But Dr. Nelson says that there really isn't much data for safe injection sites, noting that it's "largely unknown" if they're effective. "There are data to support their effectiveness, and other data that do not show any particular value," he says. "They are not inexpensive, and nobody wants them in their neighborhood, so the political costs are large. It is hard to imagine, however, that for those who choose to utilize these facilities, the risk of overdose-related death would not go markedly down."

And that's something that's needed right now. "We are in the midst of a historically unprecedented public health crisis. My research shows that in 2017, unintentional drug overdose was the third leading cause of years of life lost in the United States, just behind cancer and heart disease," Dr. Hall says. "More people died of unintentional drug overdose last year than have ever before. We must begin to experiment with new paradigms to reduce the almost unimaginable carnage we are experiencing as a nation from unintentional overdose. Safe sites have the potential to save lives. It's that simple."

Source: Read Full Article