A relaxed warmth and affection infuse the conversation as Sunil Daryanani, MD, and his son Andres Daryanani, MD, join the Zoom call from thousands of miles apart: the father from Caracas, Venezuela, and the son from Miami, Florida.

They are more accustomed to speaking Spanish together — their English is flavored with hints of a British accent — but they have chosen English today to tell the story of how Andres nominated his dad as a Medscape Oncology Hero.

“My father’s oncology practice is the reason I chose to become a physician,” Andres wrote. The 26-year-old says he does not remember a time when he wanted any other career.

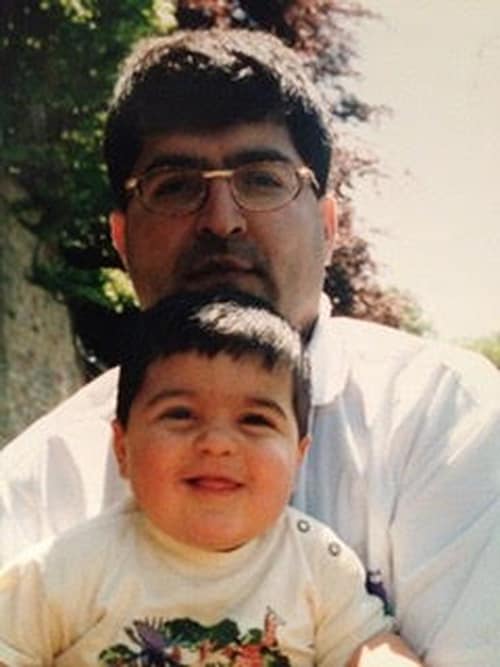

Dr Andres Daryanani (on left) with his oncologist father Sunil.

Daryanani senior listens with a smile as his son sings his praises. At the heart of Andres’ professional admiration is his father’s compassion and empathy for his patients.

In his teens, Andres would attend patients’ funerals with his dad and was struck by the families’ connection with Sunil. “There was this gratitude that came with death and knowing someone in the worst part of their life and being their ally. That struck a chord very deep inside me, and I wanted to harness that into my career,” he said.

Sunil was born and raised in Venezuela. His parents were Indian émigrés who were “hard core business people,” but he says he wasn’t interested in that kind of career. “I just felt that I had a calling of sorts in the sense that I wanted to give back, and I enjoyed engaging with people,” he explains, adding that his severe childhood asthma initially steered him toward respiratory medicine, until his first encounter with oncology.

Sunil Daryanani, MD, with a young Andreas.

After his initial medical training in Venezuela, he went to Birmingham, England, for postgraduate work, where Andres was born. “I was working crazy hours, and his mum was doing her PhD in basic sciences, so of course childcare was an issue. I used to take him along with me to hospital on Saturday mornings for my ward rounds, and the ambulance drivers would drive him around the campus with their lights on — so of course he was thrilled to bits.”

When Andres was 3 years old, his parents returned to Venezuela and divorced, but weekend ward rounds with his father continued. “I would just bring him along and have him wear my white coat and stethoscope,” says Sunil. “He saw nothing much more than what I was doing at the time, and one of the first things he ever said in English was, ‘I want to be a cancer doctor.’ “

Those early days of “pretend” matured as Sunil saw a genuine interest in medicine in his son. “When I was 5–6 years old, the fun part in the hospital was lunch in the cafeteria,” says Andres. “But then when I turned 12 or 13, my parents were a bit concerned that I hadn’t given it proper thought. So, in high school my dad started inviting me to his clinics for some of the tough conversations ― giving someone news of their diagnosis or that their treatment had failed. There’s a lot of awkwardness in how one can relate to people who have catastrophic illnesses ― maybe you try to treat them so carefully that you end up alienating them and not treating them as people but as sick people. The way my dad navigated through that…he was very empathetic. I remember crying after those conversations; it was emotionally wracking, but my dad was strong and stoic. I remember thinking, ‘I thought he was my hero, but now he really is.’ I always said, that’s what I would like to be, and that’s been a guiding force for me in medicine.”

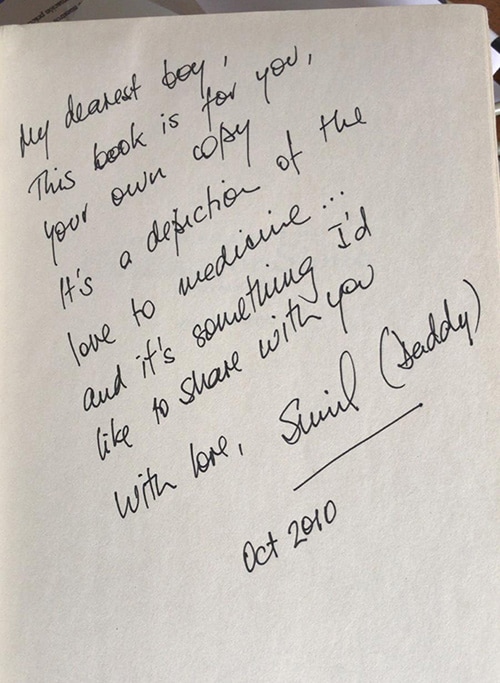

In 2013, Sunil read the novel Cutting for Stone, by Abraham Verghese. The author’s observations on the art of practicing medicine were an epiphany for Sunil, who immediately emailed Verghese an emotional acknowledgment. Verghese, also a doctor of Indian descent, is professor for the theory and practice of medicine at Stanford University Medical School, in Stanford, California.

Eventually, Verghese, Sunil, and Andres met up in California, and the author added his own inscription to that of the father’s in a copy of the book for the young doctor-to-be: “Wishing you a brilliant career in medicine, or wherever your heart takes you.”

Book dedication from father to son.

A few years later, Andres attended medical school in Bogota, Columbia, during which time his father decided to return to England. “Venezuela was going through an economic crisis and Andres was attending medical school that I needed to pay for, so I decided it was time to move,” says Sunil, who ended up in Yeovil, Somerset, before relocating to Oxford.

Midway through medical school, Andres “lost himself a bit,” his father said.

Andres recalls: “I really doubted if I had chosen the right career…. I remember feeling quite overwhelmed with how long my career path would be ― and had been so far ― and frustrated with how many of my friends outside of medicine were already starting their own lives and careers…. Life felt unbalanced and joyless, and for the first time in my life I questioned if I was meant to be a doctor.”

The crisis prompted a frank discussion between father and son. “He was really surprised when I told him I was considering a career change,” says Andres. “I was more surprised when he gave me the option to pull out.”

In the spirit of Verghese’s inscription, Sunil showed Andres an open door. “I said, if you want to do something else, maybe chef school, I’m quite happy to fund it,” says Sunil.

They both share a passion for cooking, “which Andres has taken to new heights.” But Andres insisted medicine was his calling. “Paradoxically, having the choice to do something else just made me want to finish medicine,” he recalls. “I think [Dad] played Jedi mind tricks on me, because after that, I came back more motivated and focused.”

Slowly, the balance of the relationship began to shift, as each saw the beauty of medicine through the other’s lens. Across the miles, they shared ideas and challenged each other’s perspectives. “He sent me this one paper on game theory in cancer biology,” says Sunil. “I still carry that around in shreds in my brief case. It’s such a thick paper, full of maths, and I thought, well one of these days I’ll crack it. So, I keep going back to it every so often.”

Sometimes Andres would share his assignments with his dad, “just to cast an eye,” and Sunil, who works as a reviewer for several journals, took a gentle approach. “I wanted to see his work with a lenient eye to some degree, without being overly critical.”

Not surprisingly, Andres naturally gravitated toward oncology. He saw the field with “a keener eye and a fresh look,” says Sunil. “I’ve learned through seeing things from his perspective, with that special accent to it.” Both father and son dreamed of one day having a practice together, Andres’ name under his father’s on the door plate.

But then the COVID-19 pandemic hit. It was Andres’ final year, a year that was supposed to have been filled with electives and choices. Instead, the choices narrowed to just internal medicine, anesthesiology, or pediatrics. Most of Andres’ class took the option of forfeiting the year, but Andres chose to dive in. It was the most rewarding part of his medical training up to that point. “With all the uncertainty we had in healthcare during those early months, I remember just feeling so proud to be part of the essential workforce. I had to go outside every day and see people when most couldn’t. Waking up and going to work every day had more meaning because my job wasn’t any other job, it was THE job…. I found my calling in palliative care and anesthesia. Everything sort of fell in the right places, and that career felt right with my life story and personality…. My dad’s impact in my love for medicine is unquestionable, but after COVID is when I felt it truly was my own. I traded thinking of work-life balance and joy for meaning in work, and I’m much happier and fulfilled for that.”

Dr Andres Daryanani

Andres is now preparing his applications for residency in anesthesiology, and Sunil is happy that his son has branched out on his own path. “In one sense it’s relieved me of the responsibility of whether he’s happy or not in the future — it’s all down to his own choice. I felt always the weight of his choice of medicine. Now that he’s chosen his own career path, I’m very proud.”

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article