A new study by researchers at Yale School of Medicine, McGill University, and New York University has found that people from racial and ethnic minoritized backgrounds have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic despite being more likely to engage in health and safety precautions than their white counterparts.

The study, published February 9 in JAMA Psychiatry, was co-authored by Sarah Yip, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine; Ayana Jordan, MD, Ph.D., Barbara Wilson associate professor of psychiatry at NYU Langone Health’s Department of Psychiatry and assistant professor adjunct of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine; Robert Kohler, Ph.D., postdoctoral fellow at Yale School of Medicine; Avram Holmes, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology and of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine; and Danilo Bzdok, associate professor of biomedical engineering at McGill University and at Mila Quebec AI Institute, Montreal.

“What we were able to find is that people who come from racial and ethnic minoritized backgrounds have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic and, despite what people may think, they have indeed engaged in practices to take care of themselves, like handwashing and other behaviors,” Jordan explained.

The researchers analyzed a longitudinal population cohort from The ABCD Initiative, the world’s largest long-term study of brain development and child health in the United States funded by The National Institutes of Health (NIH). Yale is one of 21 institutions recruiting families for the study. Participants were enrolled around age nine and 10, about two years prior to the pandemic.

“The kids in this cohort are going through this unique generational stressor of entering adolescence during a global pandemic,” Yip said. “We were able to see what that looks like, evaluate the impact on families, understand what is happening to these kids, and quantify that.”

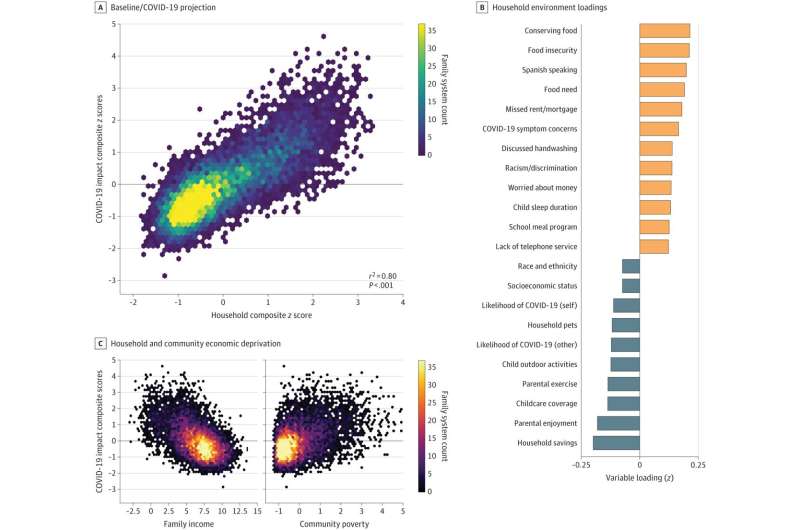

Rather than approaching the study with a specific hypothesis, researchers evaluated 17,000 individual measures included in the ABCD dataset to find the relationship between those measures and ones they had related to the impacts of the pandemic.

They found that children in non-white families had decreased access to resources and increased financial worry but were more likely to have parent-child discussions regarding COVID-19 associated health and prevention issues, like handwashing, conserving food, protecting elderly individuals, and isolating from others. Children in these families experienced impacts such as sleep disturbances and concerns about experiencing racism or discrimination related to the pandemic. Children from families experiencing increased pandemic impacts also spent more time on schoolwork but their parents report that they are less prepared for school, the data showed.

Conversely, white families with higher pre-COVID income and the presence of a parent with a postgraduate degree experienced reduced COVID-19-associated impacts, children reported longer sleep times, fewer difficulties with remote learning, and decreased worry about their family’s financial stability.

The results underscore that families most affected by inequity during the pandemic were more likely to abide by safe practices like social distancing and handwashing, despite the popular narrative that minoritized groups are less likely to engage in such behaviors, the researchers said.

Specifically, the findings indicate that community-level, transgenerational intervention strategies are necessary to combat the impact of the pandemic on these families, they said.

“The long-term costs of COVID will not play out equitably across the population. We need to put extra care into helping different groups in the population get back to where they were before the pandemic,” Holmes said.

Jordan said: “We as a country can’t continue to push individual-level behavioral change or policy change. We need to target community-level interventions that can mitigate the damage of the pandemic.”

Source: Read Full Article