It can be hard to put our health into words. We hear from four female artists who’ve decided to visualise their conditions and shine a light on what it’s really like to live with chronic illness.

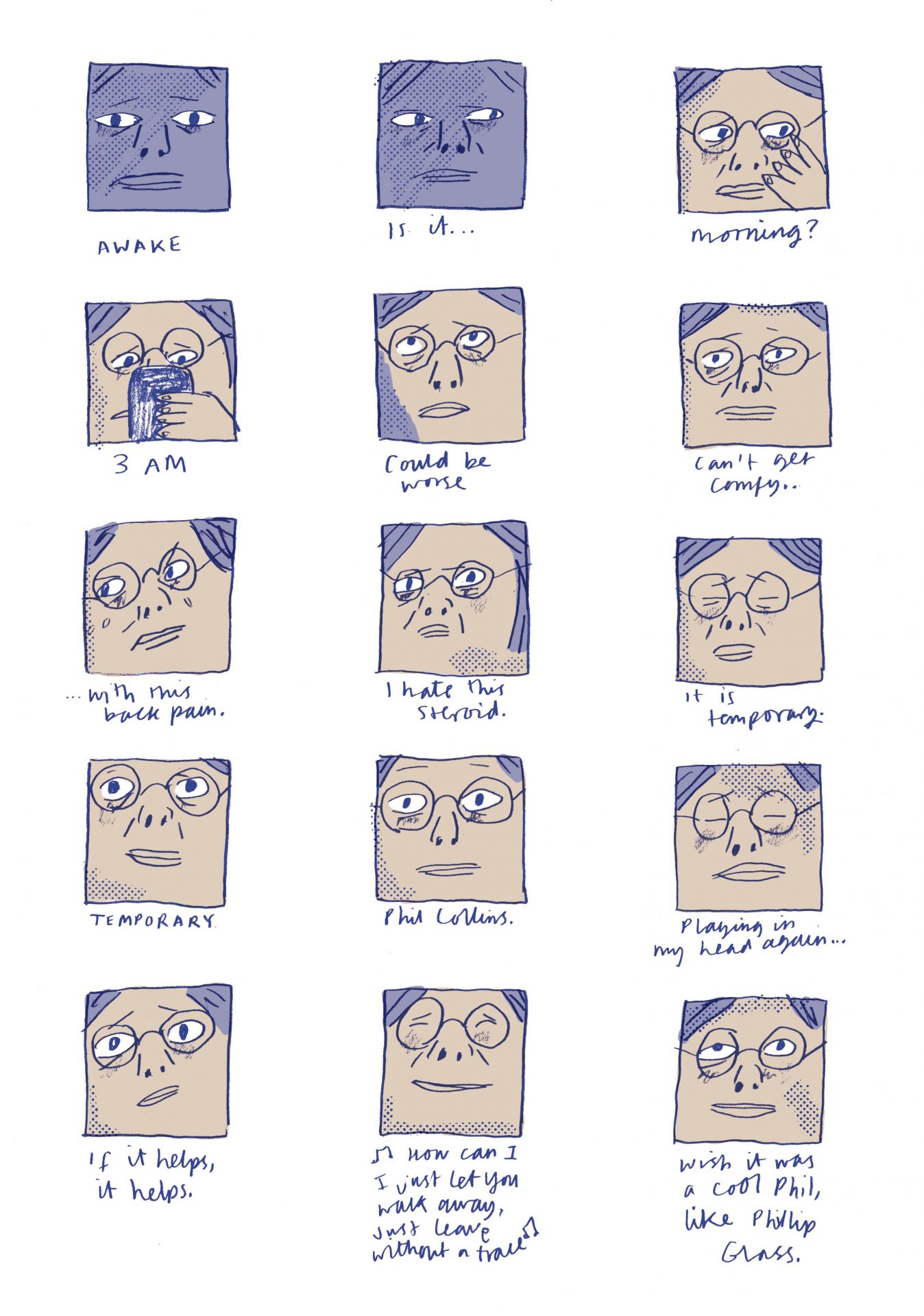

When Sarah Lippett was 18 years old she began drawing what she feared would be her last artwork.

After a childhood spent grappling with complex symptoms, undergoing brain scans and invasive tests and dealing with misdiagnosis, she had finally been diagnosed with moyamoya – a rare disease affecting one in a million people in the UK that narrows the arteries to the brain, increasing the risk of strokes.

As Lippett scribbled away in her hospital bed at Great Ormond Street, she was about to undergo lengthy brain surgery, which is the only way to treat the disease. “I gave my drawing to the nurse and told her to keep it because it could be my last piece of art,” Lippett, 37, tells Stylist. “As I sat there, I realised drawing had always been a coping mechanism. It helped me get out of my headspace. It was a real aid.”

Lippett’s symptoms first emerged when she was just seven years old, beginning as severe headaches, falling over and dragging her legs. She would spend over a decade in and out of hospital, seeing doctor after doctor, enduring long periods of time in isolation wards and receiving drugs with debilitating side effects such as urinary infections and hair loss, before finally finding answers.

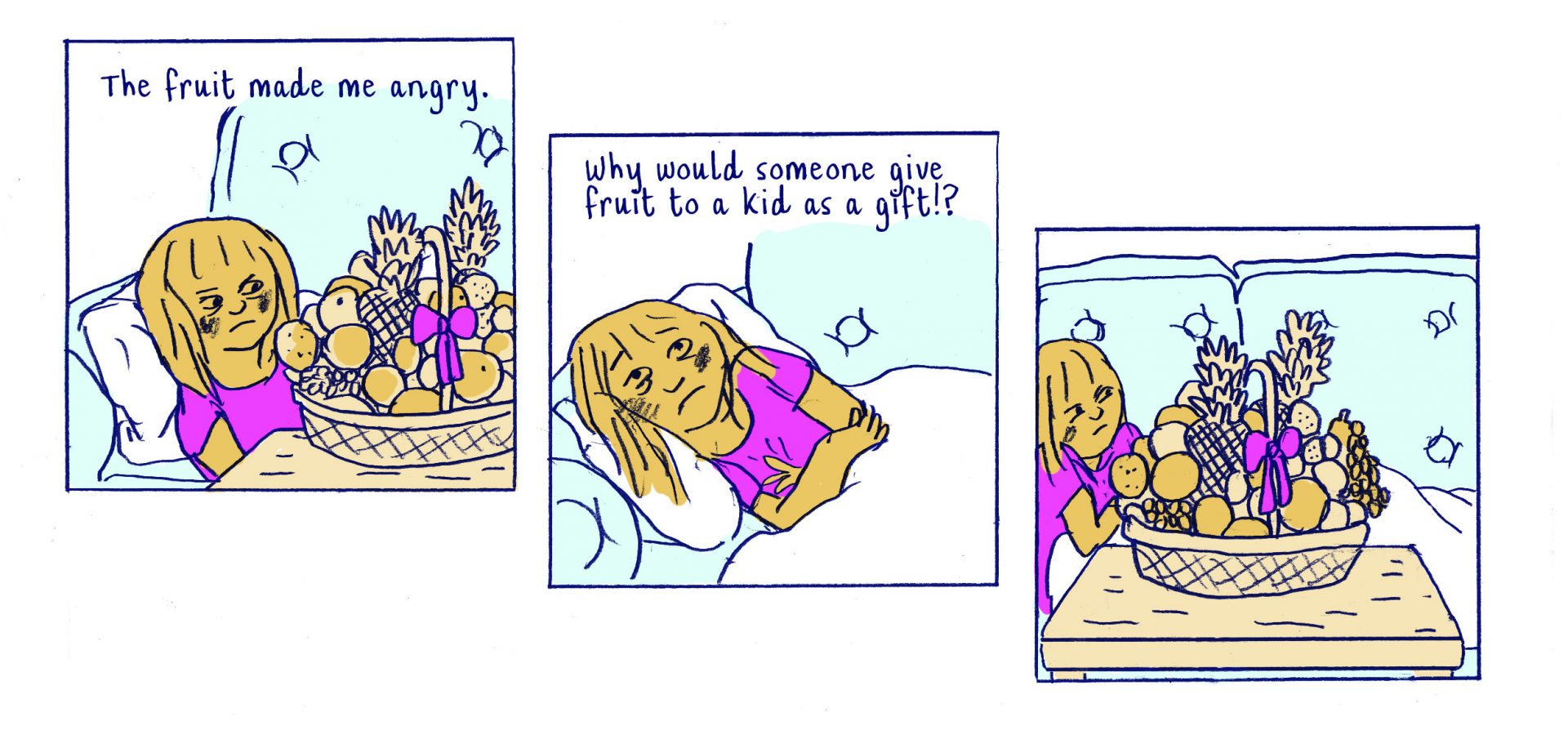

Over this time Lippett turned to art, drawing during her hospital stays and eventually going on to study illustration at university. In 2019, Lippett published her graphic memoir, A Puff Of Smoke. It tells the story of her dizzying and tumultuous childhood illness through vivid comic strips of pastel-hued illustrations (inspired by the colours of a tracksuit her dad wore when she was little) that are at once heartbreaking and humorous.

“I’d wanted to share my story for many years, but I had never been quite ready to tell it because it was a traumatic experience,” she says. “But, I felt that the diagnostic journey of patients isn’t often told and people don’t realise it can take a number of years to get diagnosed. I felt that when I was a kid, it would have been incredible to have heard another story that was similar to mine because I felt very isolated and alone.”

Lippett’s illness is so rare that when she goes to see a new doctor or a GP they turn to google to find out what it is. “If I need a doctor to better understand me, I can refer them to my book. It’s a way for people to understand what it’s like to live with a chronic illness and for doctors to see those more human stories.”

Sharing this human side has already made a difference. Lippett, who frequently gives talks at medical conferences, says she had one standout email from an anaesthetist who read her book and realised she’d forgotten what it must feel like for the patient. “She said when she treats people from now on, she’s going to think of my story,” says Lippett.“That’s enough to have written the book for.”

The gender health gap

Medicine has been male-dominated for centuries, with women’s health historically misunderstood and misidentified. From ancient Greek ideas that women’s wombs wandered through their bodies causing madness, to 19th century notions of ‘hysteria’, women have consistently been prevented or seen as unable to tell the story of their own bodies.

Even today, there is a huge gender health gap. Women are still under-represented in medical trials meaning not enough is known about conditions that only affect them, or about how conditions affect men and women in different ways.

This disparity was outlined in the UK government’s recent women’s health strategy which explained how this gap in understanding can “lead to poorer advice and diagnosis and, as a result, worse outcomes”. It’s a situation especially acute for women of colour, older women, those with disabilities and LGBTQ+ women, who are particularly underrepresented in medical research.

By transforming their experiences into art, Lippett and other female artists are railing against the stigma attached to female health. By literally creating their own picture of health, they are breaking taboos and revealing exactly what their illnesses feel and look like to them, empowering and validating other women in the process.

“Painting was a moment of peace”

Despite being “obsessed with art” as a child, it was only after Ananya Rao-Middleton, 28, had a catastrophic head injury in a go-karting accident in 2018 that she really began to get in touch with her creative side.

Her brain injury, which left her with post-concussion syndrome, meant Rao-Middleton was housebound for months. “I really couldn’t do very much at all,” she tells Stylist. “I couldn’t look at screens because they would agitate my eyes and make me dizzy. I couldn’t watch TV or text people.”

Once she got bored of listening to podcasts on repeat, Rao-Middleton decided to try watercolour painting. It was revolutionary.

“It felt like the only activity I could do that didn’t take my energy away from me,” she says. “Painting was a moment of peace. It helped me heal. When I was painting, I wasn’t trying to micro-analyse my symptoms, I didn’t feel anxious. It was therapeutic.”

Post-concussion syndrome is a condition where concussion symptoms persist for long after the expected recovery period. It can leave people with headaches, dizziness and concentration and memory issues for months, even years afterwards. Often, there are underlying causes for this. Rao-Middleton believes it was her – then undiagnosed – multiple sclerosis (MS) that made it much harder for her to recover.

In the UK, there has been very little research into post-concussion syndrome, particularly into how it affects women. “A lot of women I know within the community have really struggled for a long period of time and unfortunately I experience a lot of misunderstanding too,” says Rao-Middleton. She recounts doctors who told her to go home and rest despite her symptoms getting worse and others who told her she didn’t look sick. “I just burst into tears in front of them,” she says.

In her art, however, Rao-Middleton was able to communicate the reality of living with chronic illness and disabilities. Inspired by her South Indian heritage, her work is filled with tropical landscapes, vervet plants and deep jewel-bright colours. She also puts women of colour front and centre. “As a kid, a lot of the people I drew didn’t even look like me; they were mostly white,” she says. “So I really consciously centre women of colour to do justice to my younger self and to celebrate how incredible we are.”

“It’s exhausting to have to signpost [my illness] to people in real life. But, in my art I can express myself more honestly and connect with other people from across the disability community and help them to feel seen and heard,” says Rao-Middleton. “I used to feel a lot of resentment about my accident because someone else changed my life so dramatically, but art helped me let go of those negative emotions. It’s given me an opportunity to create something meaningful.”

Picturing pain

Gynaecology is an area of medicine that can be particularly misunderstood. Nowhere is this more clear than in the average diagnosis time for endometriosis. The condition causes tissue similar to the lining of the womb to grow in other areas of the body and despite one in 10 women of reproductive age suffering from it, it takes around seven to eight years on average for women to be diagnosed.

Ellie Pearce, 25, first started experiencing searing pains during her periods in her third year of university. It was so debilitating, she ended up quitting her job at her university library and was only able to do work for her fine art degree in short bouts. She spent her final year in and out of hospital having sigmoidoscopies and other obtrusive tests.

“I had such trouble getting a diagnosis,” she tells Stylist. The only way to diagnose endometriosis is through a certain type of keyhole surgery. “It takes so long to get to that point,” she says. “You’re passed around from doctor to doctor – it’s a really frustrating journey.”

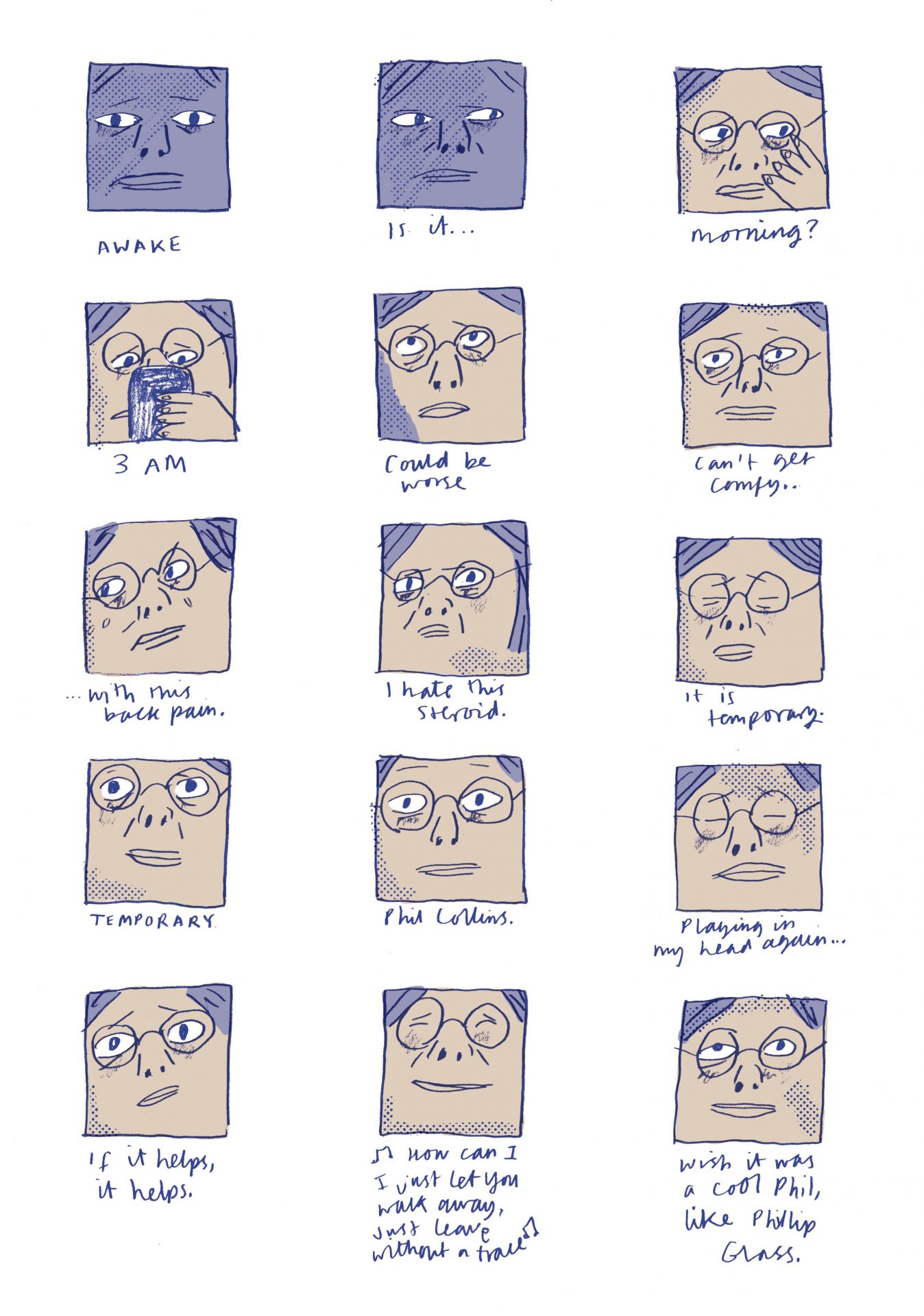

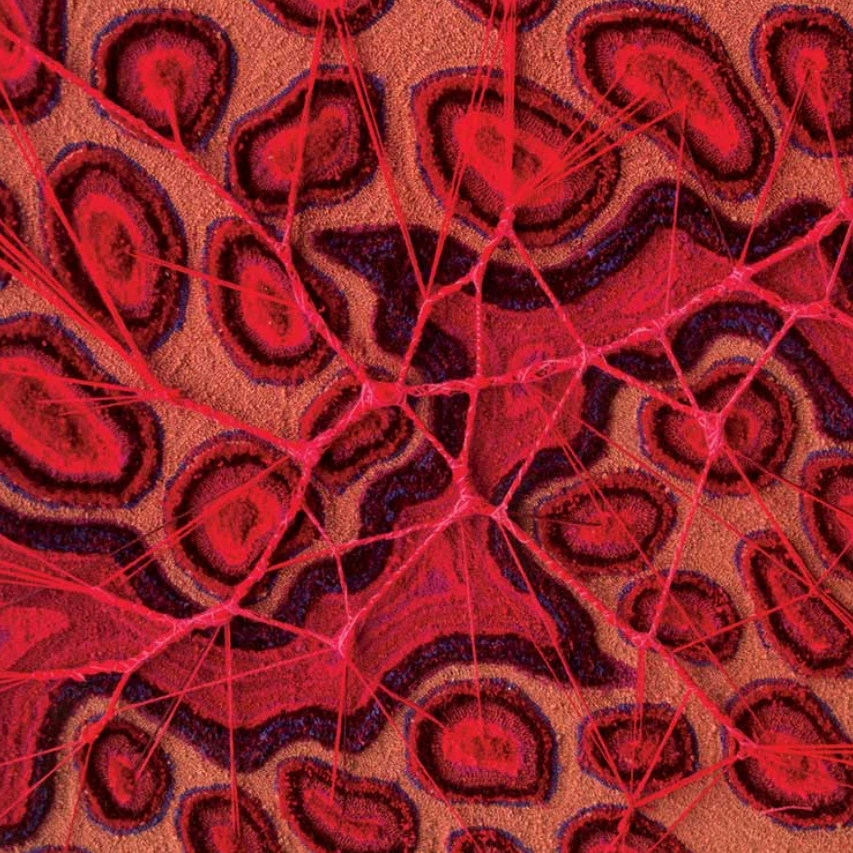

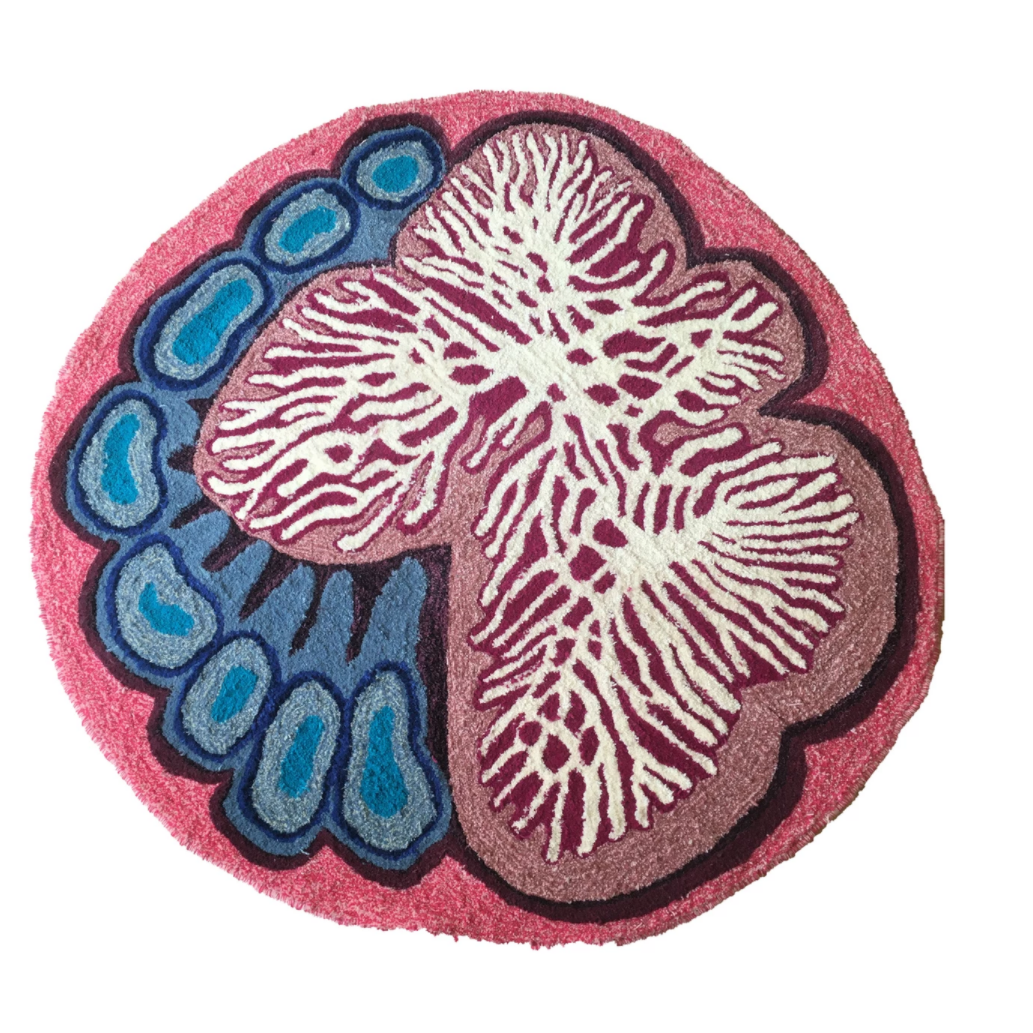

Having multiple invasive hospital scans made Pearce curious about what the inside of her body actually looked like. She began pouring over pictures of human tissue under the microscope and reimaging the patterns as colourful, tufted rugs.

“I couldn’t see what was wrong with the inside of my body. I couldn’t picture what was causing the pain. So, making the rugs was cathartic. It helped me make sense of it all,” she says. “It was comforting to make the pain into a really tactile, fluffy, soft rug.”

Pearce’s rugs, which she displayed at her final degree show, all depict different organs that can be affected by endometriosis, like the rectum and the appendix.

The pain scale is commonly used by doctors to measure a patient’s pain on a scale of one to 10, but for Pearce, it couldn’t express exactly how her endometriosis made her feel. “It’s so hard to put into words the different forms of pain you feel with endometriosis, but art is a way I can visualise it. It’s really powerful,” she says.

“Until recently, I got really upset when I spoke about my pain, but art was a way I could express it. There’s a lot of shame and stigma in talking about periods, but making my rugs made me feel powerful.”

Pills and clay

In 2017, artist Sarah Davis’ first-line treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma (a type of blood cancer) stopped working. She found out that her initial six-month-long treatment would now take a further year, and she would also have to undergo a stem cell transplant. “Suddenly, my situation became a lot more serious,” she tells Stylist. “I had to have a lot more treatment and it was going to be a long, gruelling process.”

This abrupt change led Davis to begin PUSH, an ongoing art project that she began in her bedroom while undergoing treatment. Along with plaster and clay, Davis used the materials in front of her, which at the time was lots of empty pill packets, to start making “simple” sculptures.

She started pushing the empty packets into soft, malleable blocks of clay and mixing up plaster in her bedroom to preserve the imprints. Slowly the empty pill packets became Pill Cup, which she cast in silver, then bronze, to give it a timeless quality, like an ancient relic. Then came tiles indented with rows of round and oblong pill shapes.

“A lot of people have told me they weren’t able to throw away their pill packets after being ill,” says Davis. “There’s something about holding on to them. It’s like evidence of what you’ve been through. A testament to what your body’s endured and what it’s still enduring. The pill tiles really show me the sheer amount my body’s gone through; from the acute treatment of cancer, which is the chemotherapy, radiotherapy and stem cell transplant, and then the aftermath.”

Making art gave Davis some agency in a bewildering system. “Medical trauma is a very strange form of objectification,” she says. “You’re seen as this patient and you’re signing consent forms, but you don’t have a lot of autonomy. So that’s what these artworks were – my chance to claim a bit of autonomy.”

The road to recovery

For all the artists, there remains a cloud of uncertainty about what the future of their health holds for them. For Davis, the next stages of her PUSH project will explore what it really looks like to recover from a serious illness. “My treatments can often send you into early menopause and have very long-term side effects,” she says. “There’s a difference between having cancer in the moment and then living beyond cancer. That’s what I’m interested in looking at now: the nature of recovery and whether we ever fully recover?”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Lippett. “I’m still living with my illnesses and last year I had a relapse when my kidney disease came back,” she says. “But drawing it in real-time and being able to post it on social media helped me process what was happening. Having that visual outlet saved me.”

Images: Ananya Rao-Middleton, Ellie Pearce, Sarah Lippett, Sarah Davis, Julia Bauer, Pratik Desai

Source: Read Full Article