One day, the ultrasound equipment that health care professionals use for essential diagnostic imaging may no longer be confined to the clinic, instead operated by patients in the comfort of their homes. New research marks a major step toward that future.

During the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, where hospitals in the U.S. frequently faced overcrowding, researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital set out to learn whether ultrasound scans could be self-collected by patients.

In a study published in Scientific Reports, they compared images acquired by ultrasound experts with those taken by unexperienced adult volunteers who were provided minimal guidance, finding little difference in the image quality of the two groups. The results point to ultrasound as a potential at-home diagnostic tool, where to buy zoloft now which could increase the safety and accessibility of care for patients and relieve pressure on health care facilities in trying times.

“COVID-19 forced everyone to look at unconventional solutions like this, but what we learned could be beneficial well beyond the pandemic context,” said senior author Tina Kapur, Ph.D., assistant professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School and executive director of Image Guided Therapy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Ultrasound, which transmits and receives sound waves to image our organs and tissues, is lower cost and more portable than other imaging techniques and has recently demonstrated higher accuracy in detecting certain types of respiratory disease and heart failure.

Previous research has explored the value of portable, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) for emergency medical technicians (EMTs) in the field, however, during the COVID-19 pandemic, another potential use came to light.

“We started to see these groups of physicians, who were diagnosed with COVID-19 and had access to portable ultrasounds, scanning themselves. That was the first way we saw POCUS being used regularly at home,” said lead author Nicole Duggan, M.D., director of Emergency Ultrasound Research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Duggan and her colleagues set out to learn if patients with no medical training could also obtain diagnostic-quality ultrasound images remotely. In this study, they assessed the viability of at-home POCUS among a group of 30 volunteers that had no previous experience operating ultrasound devices.

The researchers developed and provided the group a 28-slide tutorial that explained how to use POCUS to obtain quality images of one’s own lungs.

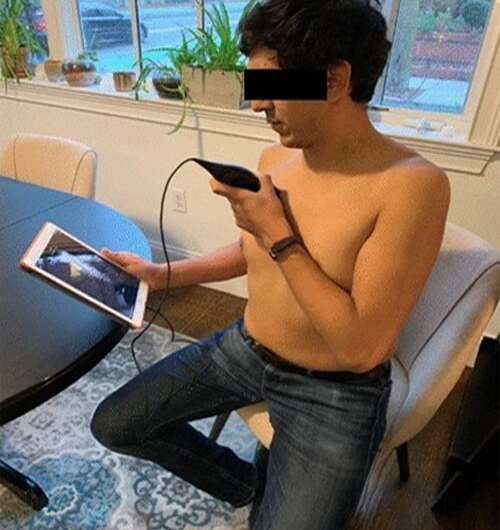

In their homes, the participants used the handheld POCUS probes, which were connected to smart devices, to scan eight zones across the surface of their chests and sides. Then, emergency medicine faculty at Brigham and Women’s Hospital repeated the imaging procedure, producing images from the same group of volunteers.

A separate pair of experts, unaware of who took which images, scored them all from zero to three based on their diagnostic quality. Assessing the scores of both novice- and expert-acquired images, the researchers found no significant differences.

“We carefully crafted the instructions to help the volunteers obtain adequate images without us by their side and the data suggests they could,” Duggan said. “As long as you communicate clearly, you can often successfully walk patients through simple protocols.”

Even with ultrasound images being taken outside of the clinic, professionals would need to evaluate images to reach any conclusions.

But still, there are clear benefits for times when emergency rooms and hospitals become overcrowded, Kapur said. And effective at-home POCUS would always be good news for patients with impaired mobility, compromised immune systems, or that live in regions with limited health care resources.

“I believe this study is an eye opener for how versatile of a technology ultrasound is. If deployed in the optimal way, it could be a game changer for telehealth applications,” said Qi Duan, Ph.D., director of the biomedical informatics program in the Division of Health Informatics and Technologies at the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB).

The study focused on images taken from healthy participants, but the authors plan to test POCUS on patients with specific diseases to find out how well the quality of patient-procured images holds up.

More information:

Nicole M. Duggan et al, Novice-performed point-of-care ultrasound for home-based imaging, Scientific Reports (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-24513-x

Journal information:

Scientific Reports

Source: Read Full Article